When I arrived at Brigham Young University as an excited freshman, my plan was to major in biology. I had really enjoyed biology in high school and scored a perfect 5 on the AP exam, so I figured this was something I could be good at. That first year I took courses in general biology, biodiversity, chemistry, and physical science.

Those courses were not at all what I had expected. They taught evolution.

My high school courses had also taught biological evolution, of course. And I had learned everything really well. But I had consistently bracketed anything to do with evolution into a separate category of my brain labeled “This is false—learn it well enough for the test but don’t buy into it!”

I had been trained that way my whole life. I remember as a little boy watching Jiminy Cricket show a caveman and sing, “You are a human animal”—right until the TV was turned off halfway through the song and I was told that we believe in Adam and Eve. After I saw Jurassic Park as an eight-year-old, we had a family discussion to discredit the movie’s repeated suggestion that modern birds descend from prehistoric reptiles. As a teenager, I came across statements in some of the Church books we kept in our home library that seemed to confirm that the restored gospel debunks the theory of evolution.

That is why I was so flabbergasted when I arrived at BYU and discovered that all my science professors continued to teach evolution just as my high school teachers had done. I had been looking forward to getting the “real scoop” from professors who shared my faith in God as Creator. I remember spending that year often feeling disappointed and confused.

Several years have passed since I entered BYU as a freshman. After my mission, I ended up switching my major to Ancient Near Eastern Studies, meaning I studied the Bible, with a particular focus on learning Hebrew and the contexts of the Old Testament. At two other universities, I received a master’s degree and a PhD in the Old Testament, after which I returned to BYU to teach in Religious Education. And although it may surprise some people, I am much more comfortable with the idea of evolution today than I was as a biology student. I attribute this shift to three primary factors: (1) an improved understanding of how official doctrine is defined in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; (2) my study of what the Old Testament does and does not say about the Creation; and (3) a growing comfort with ambiguity, complexity, and unresolved questions. I hope that this brief description of my personal journey will be helpful to others who are navigating similar questions.

Official Church Doctrine

I was born in a Latter-day Saint family, so while growing up I often heard about the importance of doctrine. I knew that there is true doctrine and false doctrine. I knew that true doctrine comes from the scriptures and from living prophets. And I knew that people of the world often “teach for doctrines the commandments of men” (JS–H 1:19).

Despite my appreciation for the beautiful doctrines of the restored gospel, I look back now and think that as a young college freshman I did not understand the parameters and limits of what can be considered official Church doctrine. That lack of clarity, in turn, only added to my confusion that year.

On May 4, 2007, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints posted an important statement to its online newsroom to clarify what is and is not official Church doctrine, and that statement has been quoted multiple times in subsequent general conference addresses. Let’s look at three of the important principles it outlines.

1. “Not every statement made by a Church leader, past or present, necessarily constitutes doctrine. A single statement made by a single leader on a single occasion often represents a personal, though well-considered, opinion, but is not meant to be officially binding for the whole Church.”

This point has been quoted in general conference by Elder D. Todd Christofferson and President Dallin H. Oaks, both of whom commented on its implications. Elder Christofferson added Joseph Smith’s explanation that “a prophet [is] a prophet only when he [is] acting as such.” As a then-member of the First Presidency, Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf also reiterated that not every idea expressed by a Church leader necessarily reflects the doctrine of the Church. “There have been times,” he explained, “when members or leaders in the Church have simply made mistakes. There may have been things said or done that were not in harmony with our values, principles, or doctrine.”

I did not understand this my freshman year. Shocked that my professors were teaching evolution, I undertook my own study to really pin down what the Church’s doctrine on evolution was, and I spent more than a semester compiling various quotes and talks. I found many statements opposing evolution by past Church leaders, and for a time that settled the matter in my mind. Since then, the teachings of modern Apostles have taught me that I need to be more careful in how I identify doctrine.

So, if any statement by any Church leader does not necessarily represent doctrine, what does?

2. “With divine inspiration, the First Presidency (the prophet and his two counselors) and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (the second-highest governing body of the Church) counsel together to establish doctrine that is consistently proclaimed in official Church publications.”

This point was reiterated in a general conference address by Elder Neil L. Andersen: “A few question their faith when they find a statement made by a Church leader decades ago that seems incongruent with our doctrine. There is an important principle that governs the doctrine of the Church. The doctrine is taught by all 15 members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve. It is not hidden in an obscure paragraph of one talk. True principles are taught frequently and by many. Our doctrine is not difficult to find.”

In a later general conference, President Oaks quoted Elder Andersen’s explanation, citing “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” as an example of a doctrinal declaration “signed by all 15 prophets, seers, and revelators.” President James E. Faust explained that the Lord has an important purpose behind this principle of a “unanimous voice” (D&C 107:27):

“This requirement of unanimity provides a check on bias and personal idiosyncrasies. . . . It ensures that the best wisdom and experience is focused on an issue before the deep, unassailable impressions of revealed direction are received. It guards against the foibles of man.”

In other words, while the corpus of official Church doctrine is much more limited when you count only what all fifteen Apostles are teaching, those teachings go through a fifteen-layer vetting process that helps ensure that the Lord’s doctrine is taught in its purity. Elder M. Russell Ballard testified that blessings come as we look to the unified teachings of those two quorums, for “when the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve speak with a united voice, it is the voice of the Lord for that time.”

To be honest, this restricted definition of doctrine can sometimes make it a little harder to figure out if something represents official doctrine—you can’t just find a single quote and say that is the official word on the matter! So if something qualifies as official doctrine only when it is taught by all fifteen Apostles, where do we find it?

3. “This doctrine resides in the four ‘standard works’ of scripture (the Holy Bible, the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price), official declarations and proclamations, and the Articles of Faith.”

Official doctrine is taught in the scriptures and official Church declarations and “is consistently proclaimed in official Church publications.” The consistency of these teachings is just as important as where the teachings are found, as continuing revelation will make some older teachings out of date. An article in the Church’s New Era magazine suggests asking the following question to help determine if something is official doctrine: “Has it recently been officially published by the Church (such as in general conference, manuals, magazines, and Church websites)? If the answer . . . is no, you can probably safely conclude that it’s not official doctrine.”

I did not understand this as a freshman, so my search for the Church’s doctrine often cast too wide a net, bringing in statements from unofficial sources, or from once-official sources that were by then much too old to be considered “recent.” But we are counseled to make sure we stay up to date with the current leaders of the Church. Elder Ballard gave these instructions to teachers:

“As you teach your students and respond to their questions, let me warn you not to pass along . . . outdated understandings and explanations of our doctrine and practices from the past. It is always wise to make it a practice to study the words of the living prophets and apostles; keep updated on current Church issues, policies, and statements through mormonnewsroom.org [now newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org] and LDS.org [now churchofjesuschrist.org]; and consult the works of recognized, thoughtful, and faithful LDS scholars to ensure you do not teach things that are untrue, out of date, or odd and quirky.”

I have grown to love the fact that Church teachings and practices can change over time. The Lord called this a “living church” (D&C 1:30), which points to its ability to grow, mature, and adapt, as living things do. As we respond to new mortal circumstances and as the Lord reveals truth “line upon line” (2 Ne. 28:30), Church teachings are adjusted and perfected. This is not a bug in our belief in prophetic revelation; this is the truth at the heart of that belief.

Official Doctrine on Evolution

I have reviewed apostolic teachings about what constitutes official Church doctrine, observing that a teaching is not doctrine just because of the position of the one who said it, that official doctrine is established by the scriptures and by the united voice of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve, and that current official doctrine is consistently taught in recent official publications.

So what, then, of evolution?

Because new revelation may come or Church leaders may issue new clarifying statements, my conclusions here are subject to revision in the future—we have been talking about staying current, after all! But as I write this article two decades into the twenty-first century, it seems to me that, at this time, the official doctrine is that there is no official doctrine.

While my parents and grandparents grew up in an era when anti-evolution statements were sometimes preached over the pulpit in Church settings, that has simply not been my experience as a Latter-day Saint millennial. I have never heard a general conference speaker decry the theories of “so-called scientists,” nor received a new manual stating that there was no death anywhere in the world before the Fall, nor read a Church magazine saying that evolution is contrary to the teachings of the gospel. While I have come across statements like these made by individual Church leaders, the vast majority were made before I was born. They do not represent recent, official statements authorized by the united voice of the Church’s leading quorums.

Tellingly, the most recent statements I can find from official Church sources are emphatically neutral with regard to evolution. “The Church has no official position on the theory of evolution,” the New Era magazine stated in its October 2016 issue. It went on to explain that “organic evolution, or changes to species’ inherited traits over time, is a matter for scientific study. Nothing has been revealed concerning evolution. . . . The details of what happened on earth before Adam and Eve, including how their bodies were created, have not been revealed.” Another article (this one featuring a painting of a feathered dinosaur) states that “the details of what happened on this planet before Adam and Eve aren’t a huge doctrinal concern of ours. The accounts of the Creation in the scriptures are not meant to provide a literal, scientific explanation of the specific processes, time periods, or events involved.”

In 2022, the third volume of the official history Saints noted that Elder John A. Widtsoe had published a series of articles intended to “reconcile gospel knowledge with secular learning,” including evolution. Saints also describes the national controversies over evolution that took place in the early twentieth century, explaining the different positions of “modernist” Christians (who allowed for evolution) and “fundamentalist” Christians (who saw human evolution as blasphemy) without choosing sides. President Heber J. Grant, Saints explains, did not feel he had to “tell people what to believe” about the issue. A Church History Topics article titled “Organic Evolution,” prepared to accompany Saints and posted to the Church’s website, similarly explains evolution in a neutral and even-handed tone. It states that “faithful Latter-day Saints [have] continued to hold diverse views on the topic of evolution” (see appendix for full text).

Of course, the Church does have official doctrine that touches on the Creation of the earth and the origin of human beings. The same Church magazine article indicating that nothing has been revealed about evolution gave this summary of what doctrine has been revealed:

Before we were born on earth, we were spirit children of heavenly parents, with bodies in their image. God directed the creation of Adam and Eve and placed their spirits in their bodies. We are all descendants of Adam and Eve, our first parents, who were created in God’s image. There were no spirit children of Heavenly Father on the earth before Adam and Eve were created. In addition, “for a time they lived alone in a paradisiacal setting where there was neither human death nor future family.” They fell from that state, and this Fall was an essential part of Heavenly Father’s plan for us to become like Him.

This same careful distinction between what we do not know and do know from revelation was also modeled by Elder Jeffrey R. Holland in general conference: “I do not know the details of what happened on this planet before [the Fall of Adam and Eve], but I do know these two were created under the divine hand of God, that for a time they lived alone in a paradisiacal setting where there was neither human death nor future family, and that through a sequence of choices they transgressed a commandment of God which required that they leave their garden setting but which allowed them to have children before facing physical death.”

This doctrine of the Creation and the Fall, as expressed by Elder Holland and other Church leaders, of course precludes certain ways of looking at the origin of life, such as the belief that everything is the result of random chance, or the assertion that humans are no different than any other species on our planet. Our belief in heavenly parents who created this earth to help us progress in a great plan of salvation means that there is great purpose and design to our experience here. But as far as the details of how that Creation was carried about, the Church has said it leaves that up to “scientific study.”

Understanding What Genesis Is (and Is Not) Doing

In addition to modern apostolic statements, my understanding of evolution as a freshman was shaped by my interpretation of ancient scripture. I read the Creation account in Genesis and concluded that it was clearly opposed to the idea of organic evolution. God designed plants and animals to reproduce “after his” or “their kind” (Gen. 1:11–12, 21, 24–25), not to turn into other things. Before Adam, “there was not a man” (Gen. 2:5), whereas evolutionists claimed a long line of hominids. Adam was told if he ate the fruit he would “surely die” (Gen. 2:17), suggesting death was not a given.

However, having gone through thirteen more years of university study, most of it dedicated to studying the Old Testament, I have come to believe that the clarity I once saw in Genesis was an illusion. When I read Genesis in a nicely printed English book, as in the image below (fig. 1), the text felt very modern, familiar, and accessible:

Figure 1

Figure 1. Genesis 1:1–2 text from the King James Bible.

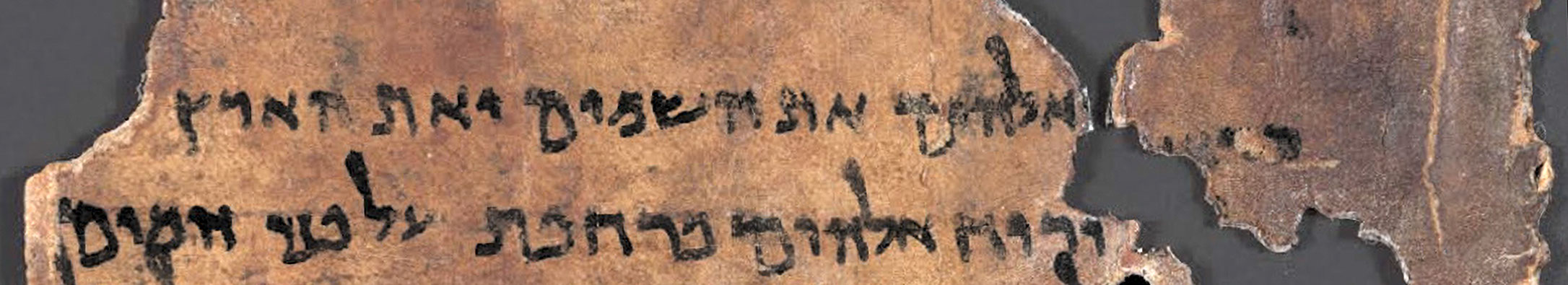

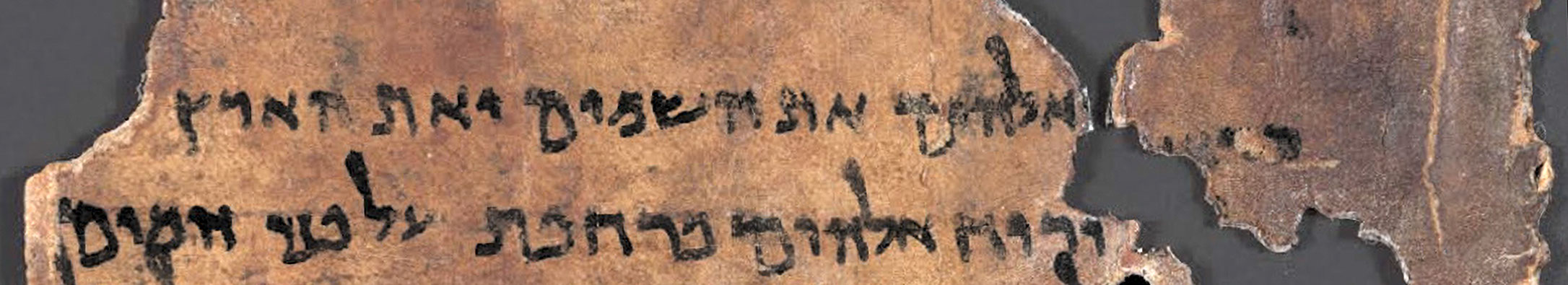

By contrast, when I think of Genesis today, it is images like this (see fig. 2) that I think of first:

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Genesis 1:1–2 as found on a Dead Sea Scrolls manuscript. “Dead Sea Scroll fragment 4Q7 with Genesis 1,” by KetefHinnomFan, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Genesis_1_Dead_Sea_Scroll.jpg, public domain.

This second image (fig. 2) is a snippet from 4QGeng, a copy of Genesis from the Dead Sea Scrolls. Unlike the first image (fig. 1), it comes from a Hebrew scroll, not an English book. It is handwritten, and although it displays Genesis 1:1–2 as in the first image, several words are missing from this fragment today due to its antiquity.

These two images are a visual metaphor for my changing perspective on the text of Genesis. Genesis is old. It was written by people who spoke and thought differently than I do. It comes from a culture far removed from my own. It has its own context and history. The handwritten manuscript also hints at the humanity involved in scriptural composition and preservation, something a cleanly printed modern book tends to obscure.

How does the foreignness of Genesis affect how we read it today? On a linguistic level, reading in English masks the complexity and richness of the Hebrew vocabulary. Words like God, created, heaven, earth, deep, Spirit, waters, day, or firmament all have their own history, nuances, and interpretive challenges, even in Hebrew. In English, it is deceptively easy to think that a word has a single, clear meaning without realizing how much is going on under the surface.

On a cultural level, the Creation account in Genesis both utilizes and reacts to cultural frameworks and cultural points of reference from Israelite society and the broader ancient Near Eastern “pop culture” that the Israelites participated in. By way of analogy, imagine someone giving a sacrament meeting talk today and saying, “Captain America may have beat the Nazis in World War II, but he’s no Captain Moroni.” That statement draws upon (1) Latter-day Saint insider knowledge, (2) American pop culture, and (3) world history, but it makes sense to any American Latter-day Saint because of our shared cultural references. Someone three thousand years from now, however, might not understand how these two captains are not alike when they share the same rank, and they might not appreciate that Captain America’s exploits are fiction even though the Nazi defeat in a world war is real history. In a similar way, there are numerous features of the Genesis Creation account that would have made perfect sense to an Israelite audience three thousand years ago but that are not clear to us now because we no longer share a common cultural frame of reference.

How do we go about recovering that lost context? To return to our hypothetical sacrament meeting statement, scholars in three thousand years who want to understand the differences between Captain Moroni and Captain America would have to read widely from Latter-day Saint scripture and engage with American pop culture—like maybe a few Marvel comics or movies. They would also need a good enough handle on twentieth-century history to recognize truth and fiction regarding World War II. That kind of wide reading would then let them go back to the sacrament meeting talk and figure out all the points of reference. Modern biblical scholars have followed this same procedure for Genesis. Not only have they studied Genesis and the rest of the Old Testament in the original Hebrew, but they also read widely from the surviving texts of Israel’s contemporary neighbors, like the Egyptians, Canaanites, and Babylonians. Reading all this comparative literature has revolutionized our understanding of Genesis because now a lot more of the assumed cultural references suddenly make sense.

What have we found from studying texts like Genesis 1 in context? There is not space here to get into much detail, but the super short version is that Genesis is not primarily interested in revealing the physical processes by which the earth was formed and life came to be. The concern, rather, is theological. The cultures around the Israelites believed many things about God and the world that Genesis considers to be false, and Genesis wants to explain how things really are. Here are paraphrases of some of the ideas being taught by the Israelites’ neighbors:

• “The gods don’t care about humans.”

• “Creation couldn’t happen until the creator god defeated the forces of chaos in a tremendous battle.”

• “Divine beings often quarrel among themselves.”

• “We are nothing like the gods.”

• “The greatest god is Marduk/Baal/Ra/etc.”

• “Who knows why the gods do what they do?”

The revealed truths in Genesis 1 push back against these ideas. The God of Israel is the Creator, not Marduk or Baal or Ra. There is only one God who rules the cosmos, not many gods competing with each other for position. Creation was not the result of an epic divine battle, but rather God commanded, “Let there be!” and creation obeyed. Human beings are not an afterthought but the entire purpose of Creation. God created humans in his image and revealed himself to them from the beginning.

Genesis 1, then, is trying to answer questions about God and his relationship to human beings. It is not interested in answering my modern questions about the age of the earth or human evolution or tectonic plates—the Israelites would not have even understood those questions, let alone the answers, nor would they have found them to be important.

Using Genesis to learn about physical creation from a modern, scientific point of view has other challenges. Perhaps none is greater than this: not only is Genesis 1 not interested in describing the physical universe from a modern, scientific point of view, but it deliberately utilizes ancient Near Eastern models of the universe that we know are inaccurate.

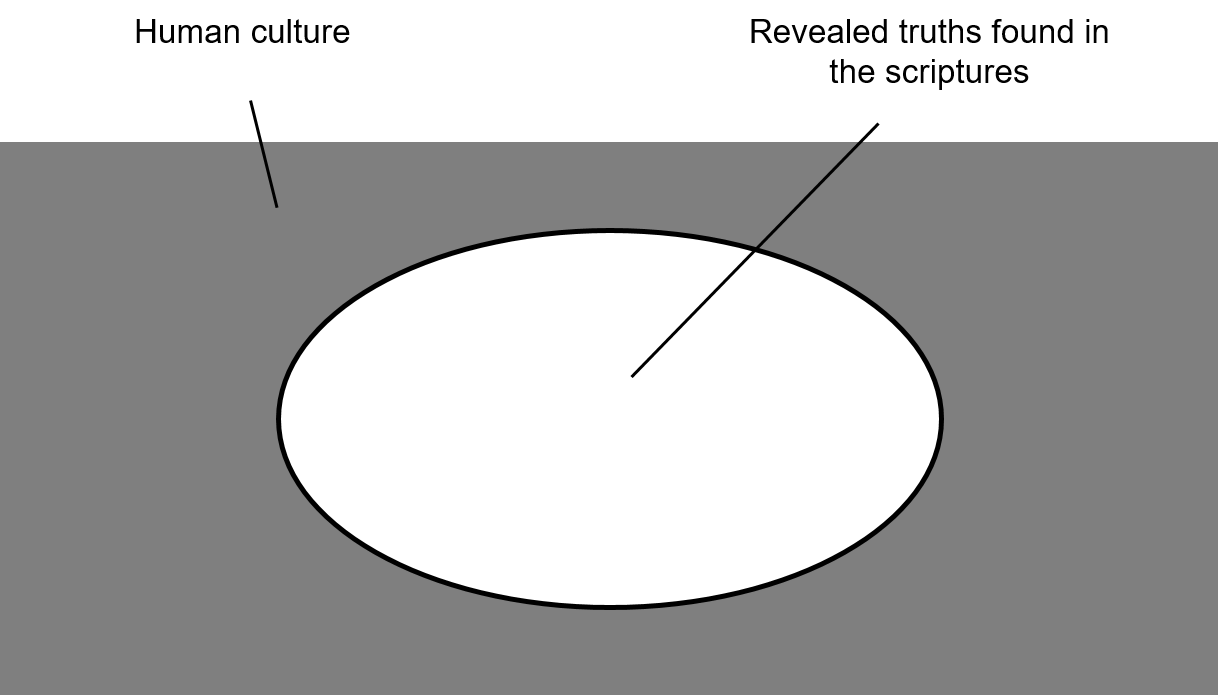

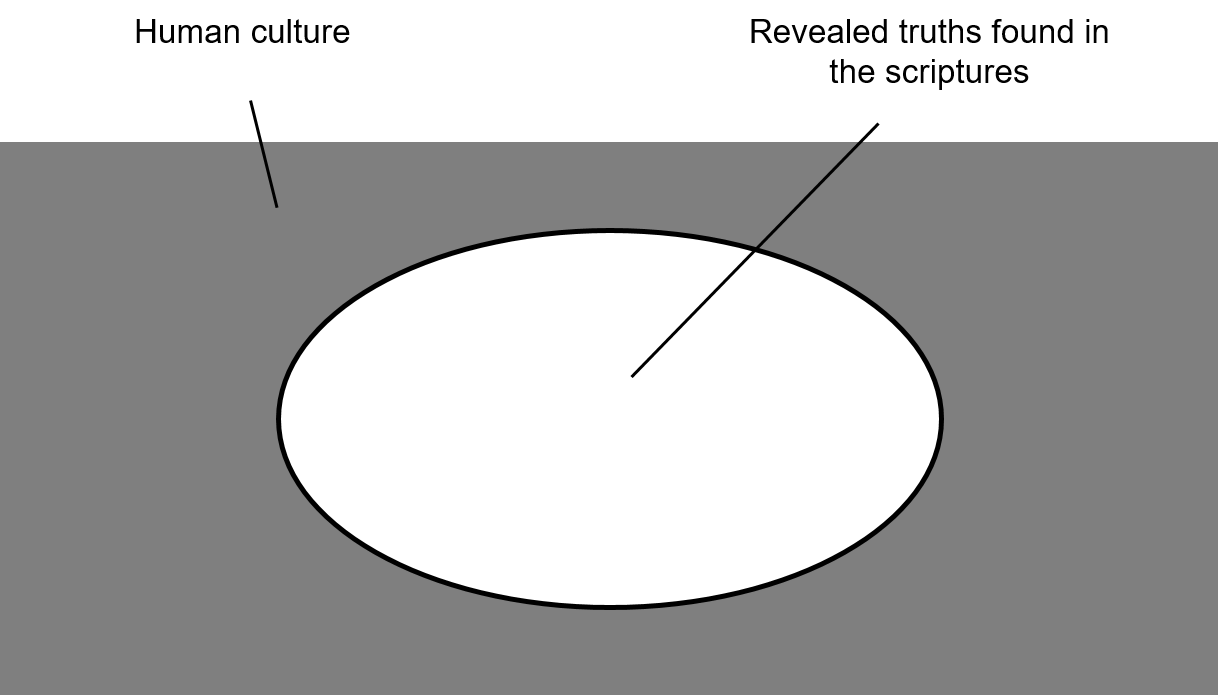

To explain what I mean, we need to think carefully about how revelation works. The diagram below (see fig. 3) represents the way many people imagine the relationship between revealed knowledge and human culture. The dark gray area represents the human cultural environment surrounding us—the customs and beliefs and assumptions and practices of the world at large. Revealed truth, as represented by the white space in the middle, is completely separate from the philosophies of men and other cultural errors. The two sources of knowledge are completely distinct inasmuch as revealed truth comes from a God who knows all truth in its fulness and purity.

Figure 3

Figure 3. One way to visualize the relationship between revealed knowledge and human culture is to see them as completely distinct.

Although revelation is often assumed to work this way, I don’t think that illustration can explain everything we find in the scriptures, nor does it match how the scriptures describe their own nature. In modern revelation, the Lord explained, “Behold, I am God and have spoken it; these commandments are of me, and were given unto my servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding” (D&C 1:24). In other words, God wants to be understood, but with all his infinite power and wisdom, he cannot speak truth in its full perfection and expect us to be able to understand. Instead, he adapts the manner of his language to match our own and speaks to accommodate for our human weakness.

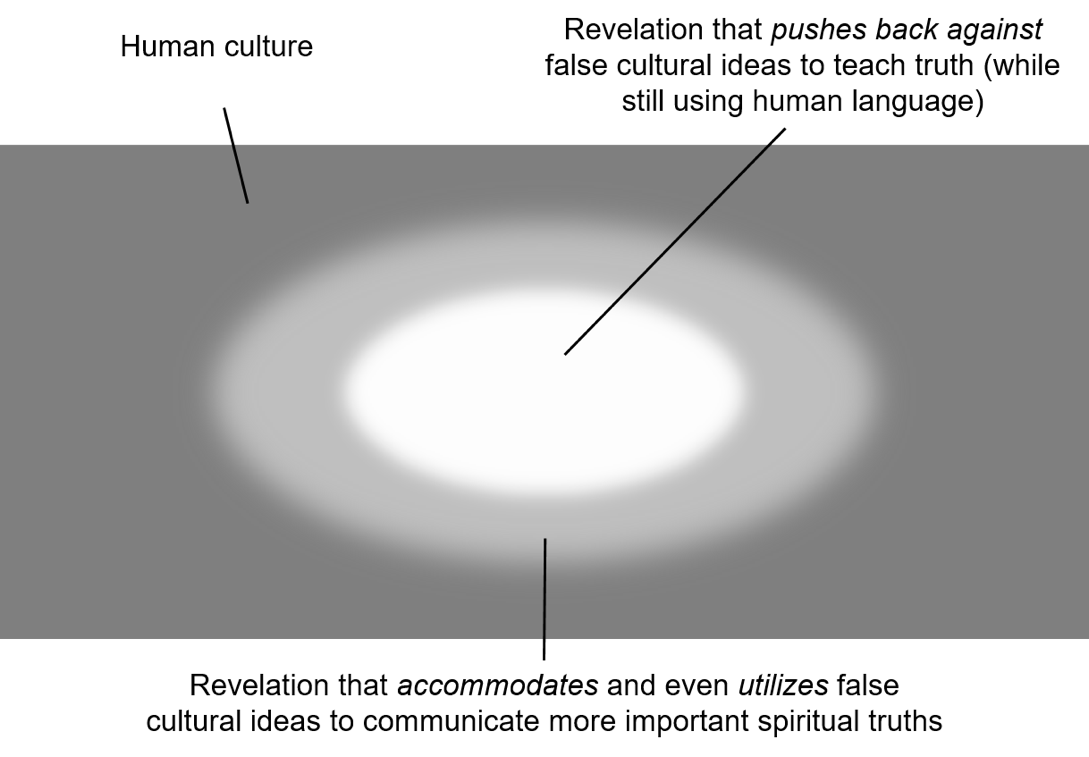

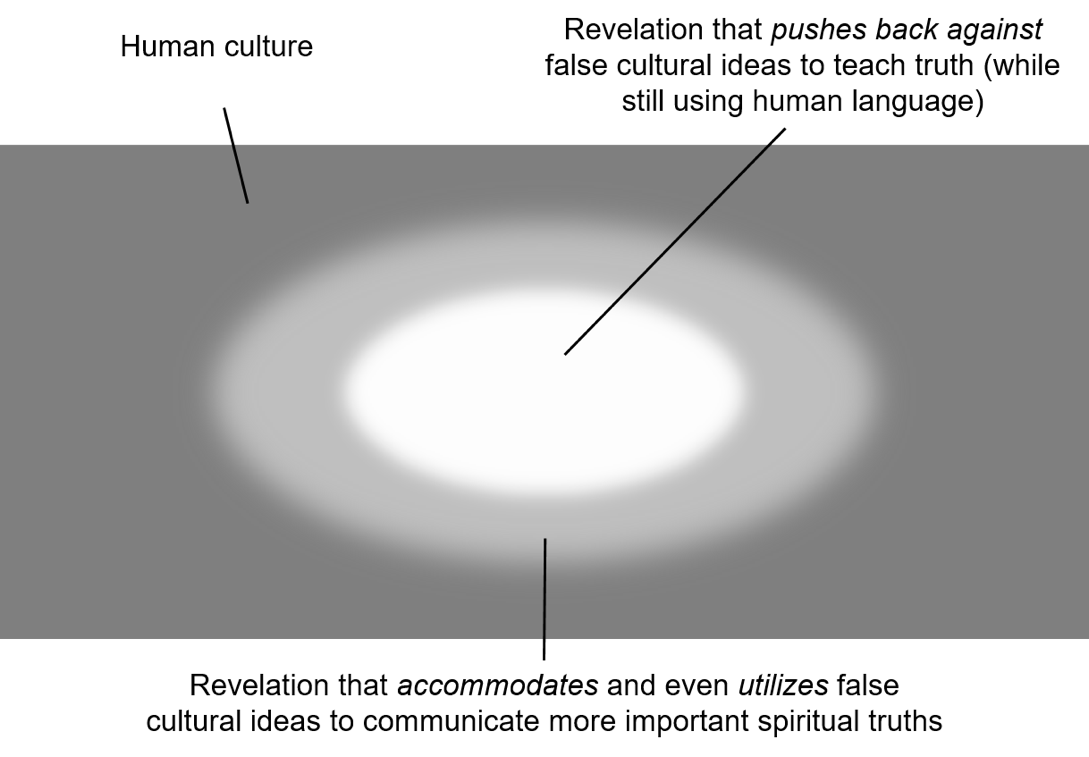

In the modified diagram below (see fig. 4), the dark gray area still represents human culture, along with all of its assumptions and ideas, good or bad. But in this representation, I have separated revealed truth into two categories. In the middle is revelation that “confound[s] false doctrine” (2 Ne. 3:12) by pushing back against false human ideas. These revelatory truths contrast with the ideas of the world, but they are not completely separate from human thought either; at a minimum, such revelation must still conform to “the manner of their language” (D&C 1:24), so I’ve left it slightly gray in the diagram. Next is a category of revelation I have depicted as light gray, representing an even greater accommodation of divine revelation to human perspectives. This manner of revelation not only conforms to human language but also utilizes cultural models, assumptions, and ideas as vehicles for communication—including cultural models, assumptions, and ideas that may be wrong. Such revelation is adapted to human “weakness” (D&C 1:24), sacrificing some accuracy in order to convey more important spiritual truths. Thus, this modified diagram recognizes that there is no sharp division between human culture and divine revelation, for divine revelation is filtered to some degree or another through the limited capacity of human understanding.

Figure 4

Figure 4. Another way to visualize the relationship between revealed knowledge and human culture is to see God as utilizing human frameworks to communicate with us.

Here is how we might map this framework onto a scriptural text like Genesis 1, our classic account of Creation. As we discussed above, some aspects of Genesis 1 push back against incorrect cultural ideas (as in the mostly white space in fig. 4). In other ways, however, Genesis 1 taught the Israelites not by contradicting the incorrect ideas of their cultural environment, but by accommodating and using them (as in the light gray space). The revealed text utilizes an incorrect but then-common model of the physical universe (a “cosmology”) in order to teach spiritual truths.

Here is a quick summary of that model: As depicted in the Old Testament, the earth is a flat disc, with its land resting on watery depths (“the great deep”; Gen. 7:11; see Gen. 1:2; 8:2). A solid hemisphere (the “firmament”) rests above it like an upside-down bowl (Gen. 1:6–8; Ex. 24:10; Job 37:18; Ezek. 1:22), and above that is a watery environment (“the waters which were above”; Gen. 1:7), with the firmament keeping it from crashing down on earth (Ps. 148:4–6). However, gaps can open up in the firmament (“the windows of heaven” Gen. 7:11; 8:2; 2 Kgs. 7:2; Mal. 3:10; see also Isa. 24:18), which allow water to come through in the form of rain. The sun, moon, and stars move “in the firmament,” or underneath the solid dome, to provide light to the dry land below (Gen. 1:14–18).

Why would God choose to accommodate the Israelites’ inaccurate model of the universe instead of correct it? My honest answer is that I don’t know. If I had to guess, however, I would start by asking what good that would have done. Most ancient Israelites were simple farmers or shepherds. They worked hard from sunup till sundown. Many would never have traveled very far from where they were born. They never looked in a telescope or a microscope. If God had tried to explain solar systems and black holes and nuclear fusion, could they possibly have understood it? And what would have been gained for the effort? I imagine that God had much more important things he wanted them to understand (such as their place in Creation and its goodness), and their existing cosmology, inaccurate as it may have been, worked just fine as a vehicle through which to teach those more important spiritual truths.

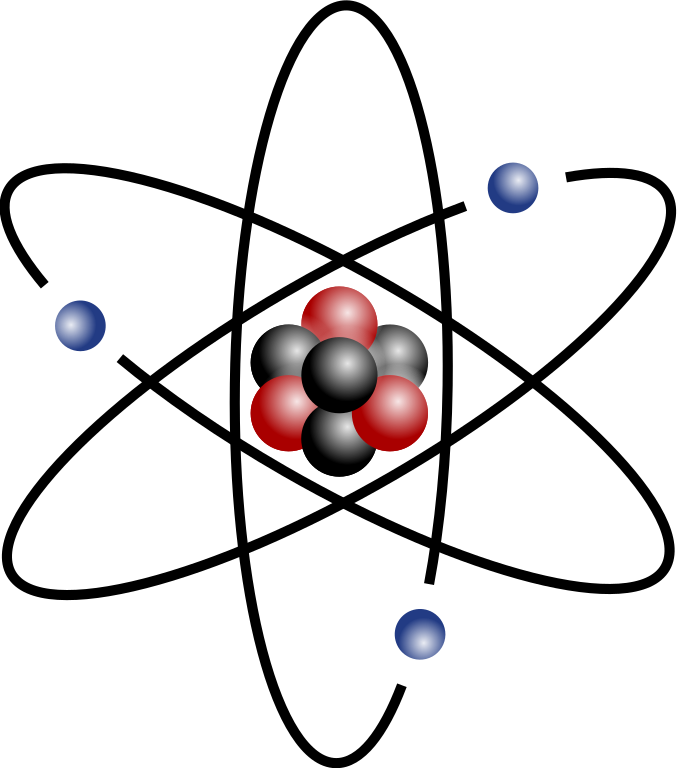

Here is a personal story by way of analogy. In my high school science classes, I was taught that atoms look something like figure 5:

Figure 5

Figure 5. The Bohr model of the atom. “Stylised atom with three Bohr model orbits and stylised nucleus,” by Indolences, modified by Rainer Klute, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stylised_atom_with_three_Bohr_model_orbits_and_stylised_nucleus.svg, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

This is called the Bohr model of the atom, and the basic idea is that you have the nucleus in the middle with electrons orbiting like planets do around the sun. I remember being taught how to use this model to calculate, for example, which atoms would come together to form molecules.

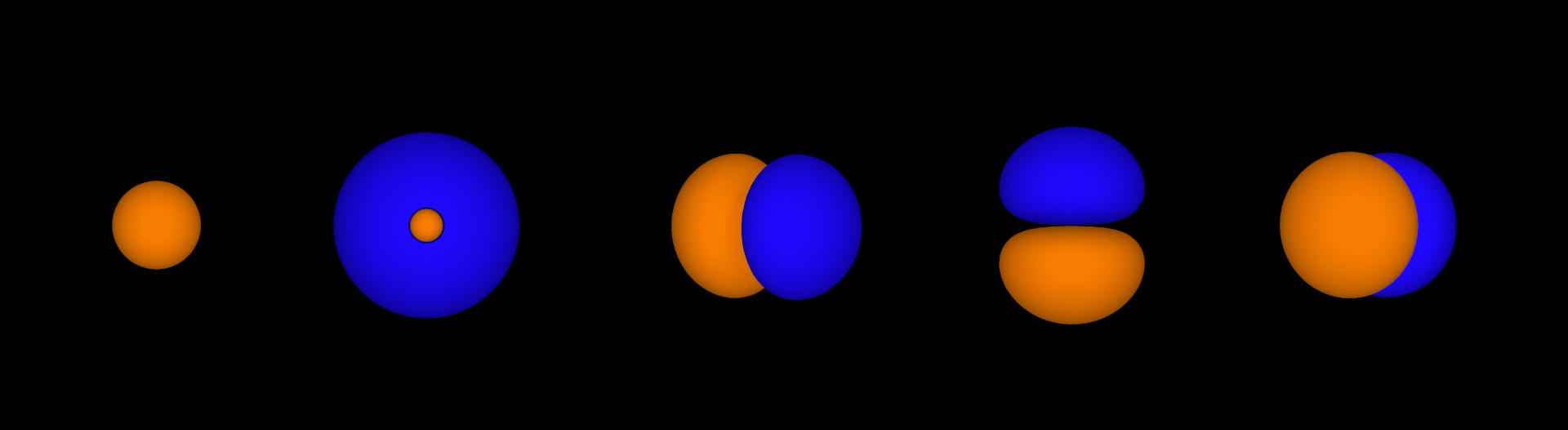

Then I got to BYU and took Chemistry 105. There I learned that the Bohr model is inaccurate and in fact was obsolete as early as the 1920s. Instead of orbits, electrons actually move unpredictably through sets of probability clouds, like in figure 6:

Figure 6

Figure 6. The valence shell model of the atom. “Neon orbitals,” by Rakudaniku, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neon_orbitals.png, public domain.

I remember feeling really confused. Why had my high school teacher taught me a model that was wrong? Our class teaching assistant had an answer: despite its limitations, the Bohr model is (1) easier for high school students to quickly grasp and (2) is actually quite useful for making a number of basic predictions. It reaches a point where it stops being useful (thus we now have quantum physics), but it gets the job done for beginners. As one high school chemistry teacher explained, “Even [information] that is somewhat wrong can be enormously useful.”

The cosmology in Genesis 1 is wrong, but I think that for the ancient Israelites it was still useful. It allowed God to teach them about himself and his purposes for Creation in a way that made sense to them. It is an example of revelation “given unto [God’s] servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding” (D&C 1:24). So when we ask if Genesis 1 is “wrong,” we have to be careful to define what we mean by wrong. If we are speaking in terms of modern, scientific principles of planetary formation, then yes, it is wrong. But that is not what Genesis 1 is even trying to do. If its primary purpose was to teach the ancient Israelites who God was and what their relationship was to him, then Genesis 1 succeeds beautifully.

Let’s bring this all together now. I began by saying that as a freshman I read Genesis and thought it clearly spoke against evolution. Now I think it is very problematic to use Genesis that way. Genesis was not written to answer my modern questions about the age of the earth, or dinosaurs, or Adam’s relationship to other hominids. The ancient Israelites would not have even understood those questions. Rather than a scientific treatise in the modern sense, Genesis is a revelatory text answering the ancient Israelites’ spiritual questions, and we risk misusing it if we try to make the text do something it was not designed to do. The fact that it chooses to adopt an inaccurate ancient Near Eastern cosmology is even more reason to be cautious about trying to read it as a modern textbook on geology or biology.

Ambiguity, Complexity, and Unresolved Questions

While I was too quick to conclude that the doctrine of the Church and the scriptures are unambiguously opposed to evolution, that does not mean that making sense of evolution has ever been simple. I still have so many questions and have not yet figured everything out. But in comparison with my freshman self, today I am much more comfortable living with ambiguity, complexity, and unresolved questions. When I wrestled with evolution as a freshman, I could not see how the scriptural and prophetic teachings on Adam and Eve could be reconciled with the idea that life has been gradually developed over billions of years. Because I could not see any way to harmonize those ideas, that was evidence for me that either the scriptures were wrong or that the scientists were wrong. (Given that choice, I chose to believe the scriptures.) Today, trying to reconcile these ideas still leads to a lot of unanswered questions. I have had people ask me, “If, theoretically speaking, God did create life on earth through a process of evolution, how does that work with the doctrine of the Fall?” My answer would be that, in all honesty, I have no idea. But unlike my freshman self, I no longer take my inability to explain how this would work as sure evidence it couldn’t work.

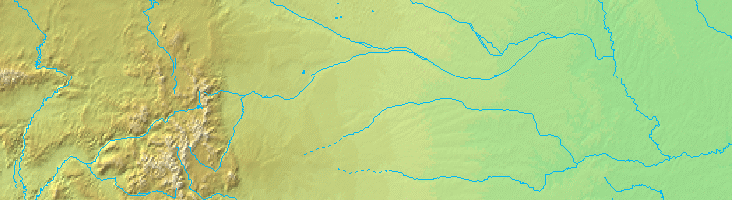

I am big on analogies, so here is another—take a look at these two maps below (figs. 7 and 8):

Figure 7

Figure 7. A map showing state borders. “Blank US Map (states only) 2,” by Jamesy0627144, modified by Szmenderowiecki, cropped, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blank_US_Map_(states_only)_2.svg, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

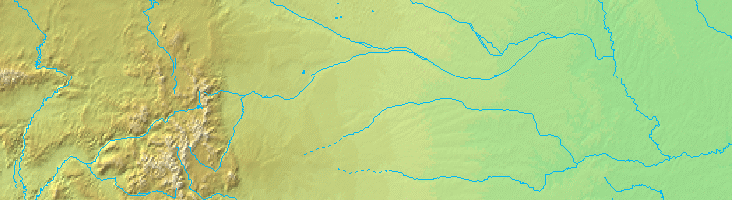

Figure 8

Figure 8. A map showing the physical landscape. “Topographical map of the United States of America,” by demis.nl, cropped, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Topographic_map_of_the_USA.png, public domain.

These two maps use state borders and topography respectively to represent the exact same area inside the United States. But because they are answering different questions (“Where are the divisions between states?” versus “What physical features are present?”), the answers each map provides do not appear to be aligned. In fact, the maps may look completely incompatible, like they are not representing the same area at all. In a similar way, it is at least possible that evolution as described by scientists and the Fall as described in the scriptures both accurately describe how humans got started, but the answers they provide look different because they are responding to different questions. Reconciling these different questions and answers may not be possible given our current limited knowledge about either scientific evidence or God’s revelations, but that does not mean that they cannot be reconciled someday.

As I have come to realize, there are actually many fundamental gospel doctrines I cannot explain in scientific terms. I believe in the reality of the Resurrection, but I do not know how the physical components that make up my body will be brought together and perfected. I have experience receiving answers to prayer, but I cannot explain how God is able to speak to my mind and heart. And despite the fact that I believe in him, teach about him, and have felt his power on many occasions, I really have no idea how the Atonement of Jesus Christ works. The scriptures testify of the reality of the Savior’s sacrifice, and they teach how I can draw upon his healing and saving power, so I am not particularly concerned that I cannot comprehend the metaphysics of it all.

These kinds of limitations are a natural part of our mortal experience where we cannot “comprehend all the things which the Lord can comprehend” (Mosiah 4:9). Even with all that we know, I have come to appreciate Elder Ballard’s counsel that sometimes it is “perfectly all right to say, ‘I do not know.’”

Conclusion

Speaking of not knowing, I still don’t know how exactly God created the earth; introduced plant and animal life; and sent his spirit children, Adam and Eve, to live here. On these questions, I am still a seeker. But since my freshman year, I have learned that the Church does not consider evolution to be a doctrinal matter and has said that this is a matter for science to answer. Given that, I am inclined to let the many intelligent men and women who work in those fields help me better understand what evidence has been left in the earth for us to find. I am aware that some Church leaders in the past have said that evolution is incompatible with the doctrine of the Fall, but although I take their concerns very seriously, I also recognize that their opinions do not represent the united voice of the current First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve. My own study of the Old Testament has also led me to appreciate the ancient context in which Genesis was created and its limitations for answering my questions in modern, scientific terms. As I continue to study these issues, I strive to seek wisdom “by study and also by faith” (D&C 88:118), ignoring neither the best books nor the voice of the Spirit. Rather than feel frustrated at what I still don’t know, I feel incredibly thankful for the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ, which has richly blessed me with knowledge of my heavenly parents and their great plan of happiness. However the world was created, I know who my Creator is, and however God’s children got here, I know we can all return home someday.

Appendix: Organic Evolution

Figure 1. Genesis 1:1–2 text from the King James Bible.

Figure 1. Genesis 1:1–2 text from the King James Bible. Figure 2. Genesis 1:1–2 as found on a Dead Sea Scrolls manuscript. “Dead Sea Scroll fragment 4Q7 with Genesis 1,” by KetefHinnomFan, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Genesis_1_Dead_Sea_Scroll.jpg, public domain.

Figure 2. Genesis 1:1–2 as found on a Dead Sea Scrolls manuscript. “Dead Sea Scroll fragment 4Q7 with Genesis 1,” by KetefHinnomFan, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Genesis_1_Dead_Sea_Scroll.jpg, public domain. Figure 3. One way to visualize the relationship between revealed knowledge and human culture is to see them as completely distinct.

Figure 3. One way to visualize the relationship between revealed knowledge and human culture is to see them as completely distinct. Figure 4. Another way to visualize the relationship between revealed knowledge and human culture is to see God as utilizing human frameworks to communicate with us.

Figure 4. Another way to visualize the relationship between revealed knowledge and human culture is to see God as utilizing human frameworks to communicate with us. Figure 5. The Bohr model of the atom. “Stylised atom with three Bohr model orbits and stylised nucleus,” by Indolences, modified by Rainer Klute, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stylised_atom_with_three_Bohr_model_orbits_and_stylised_nucleus.svg, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Figure 5. The Bohr model of the atom. “Stylised atom with three Bohr model orbits and stylised nucleus,” by Indolences, modified by Rainer Klute, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stylised_atom_with_three_Bohr_model_orbits_and_stylised_nucleus.svg, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Figure 6. The valence shell model of the atom. “Neon orbitals,” by Rakudaniku, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neon_orbitals.png, public domain.

Figure 6. The valence shell model of the atom. “Neon orbitals,” by Rakudaniku, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neon_orbitals.png, public domain. Figure 7. A map showing state borders. “Blank US Map (states only) 2,” by Jamesy0627144, modified by Szmenderowiecki, cropped, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blank_US_Map_(states_only)_2.svg, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Figure 7. A map showing state borders. “Blank US Map (states only) 2,” by Jamesy0627144, modified by Szmenderowiecki, cropped, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blank_US_Map_(states_only)_2.svg, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Figure 8. A map showing the physical landscape. “Topographical map of the United States of America,” by demis.nl, cropped, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Topographic_map_of_the_USA.png, public domain.

Figure 8. A map showing the physical landscape. “Topographical map of the United States of America,” by demis.nl, cropped, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Topographic_map_of_the_USA.png, public domain.