Notes

1. “Book of Abraham,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 9 (March 1, 1842): 705.

2. See, for instance, James R. Clark, The Story of the Pearl of Great Price (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1955), 127; Richards Durham, “‘Zeptah-Egyptus’, a New Chapter in the Study of the Book of Abraham,” 1958, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; and Walter L. Whipple, “An Analysis of Textual Changes in ‘The Book of Abraham’ and in the ‘Writings of Joseph Smith, the Prophet’ in the Pearl of Great Price” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1959), 54–56.

3. Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2018), 199, 211, 227.

4. Jensen and Hauglid, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 199, 211, 227.

5. The god Ptah was “one of the oldest of Egypt’s gods,” with evidence for his worship as far back as the Early Dynastic Period (ca. 3100–2700 BC). Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Egypt (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 123; Jacobus Van Dijk, “Ptah,” in The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion, ed. Donald B. Redford (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 322. Among his other attributes, Ptah was imagined early on as a craftsman and creator god and was later associated with Nun and Nunet, the godly personifications of the primeval waters of creation. Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 182. This may have significance for the Book of Abraham’s depiction of Egypt being “under water” when it was first discovered by Zeptah and her family.

6. Hermann Ranke, Die Ägyptischen Personennamen (Glückstadt, Ger.: Verlag von J. J. Augustin, 1935), 1:282, 288.

7. Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004), 181; Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of Ancient Egypt (Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 243–44; Ronald J. Leprohon, The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 124. The name is also attested much later in the Neo-Babylonian period. A. C. V. M. Bongenaar and B. J. J. Haring, “Egyptians in Neo-Babylonian Sippar,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 46 (1994): 70.

8. Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 56; Erich Lüddeckens, Demotisches Namenbuch, Band 1, Lieferung 12 (Wiesbaden, Ger.: Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 1993), 900–905.

9. James P. Allen, Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, 3rd rev. ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 19.

10. Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian, 34.

11. See the discussion in Hugh Nibley, Abraham in Egypt, 2nd ed., ed. Gary P. Gillum, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 14 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies at Brigham Young University, 2000), 526–39; compare Manetho, Aegyptiaca, 1.5.

12. “The transmission of [ancient] documents allowed for updating of language,” including place names and personal names. John H. Walton and D. Brent Sandy, The Lost World of Scripture: Ancient Literary Culture and Biblical Authority (Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Academic, 2013), 32. This is seen in the Bible where the names of two of King Saul’s sons are given as Ishbosheth and Mephibosheth in 2 Samuel but are rendered Eshbaal and Meribbaal in 1 Chronicles. While not all scholars agree on the meaning of this divergence, many think the baal (as in the god Baal) element was deliberately replaced by scribes with bosheth (the Hebrew word for “shame”). See the discussion in Michael Avioz, “The Names Mephibosheth and Ishbosheth Reconsidered,” Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 32, no. 1 (2011): 11–20. City names might also be updated by scribes so that the older name is given along with the name the city was known by at the time the scribe was working. This is seen in Judges 18:29: “They named the city Dan, after their ancestor Dan, who was born to Israel; but the name of the city was formerly Laish.” Examples of Egyptian scribes actively “updating” and “expanding” the language of older texts, including names and epithets, can also be cited. See, for instance, Emile Cole, “Interpretation and Authority: The Social Functions of Translation in Ancient Egypt” (PhD diss., UCLA, 2015), 167–71, 201–5; and the discussion in Emily Cole, “Language and Script in the Book of the Dead,” in Book of the Dead: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt, ed. Foy Scalf (Chicago: Oriental Institute, 2017), 41–48.

13. Jensen and Hauglid, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 292 n. 78.

14. Jensen and Hauglid, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 261.

15. One author has suggested that the name was changed “for consistency,” since Joseph had already “translated or transliterated the name of the country as Egypt.” This makes sense, because “Joseph Smith was translating the papyrus into English for readers who were already commonly familiar with this nomenclature.” Clark, Story of the Pearl of Great Price, 127, emphasis in original. Another possibility is that the change was made because the Prophet or one of his clerks had come to view Zeptah and Egyptes as the same person. The story seems to still work if they are viewed as the same person, but the textual history makes it seem more likely that these are two different women. For another proposed explanation for this change, see Brent Lee Metcalfe, “The Curious Textual History of ‘Egyptus’ the Wife of Ham,” John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 34, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2014): 1–11.

16. See, for instance, Ranke, Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, 1:285, 289.

17. Kim Ryholt, “The Late Old Kingdom in the Turin King-list and the Identity of Nitocris,” Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 127 (2000): 87–100.

18. Vivienne G. Callender, “Queen Neit-ikrety/Nitokris,” in Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010/2011, ed. Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, and Jaromír Krejčí (Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, 2011), 256.

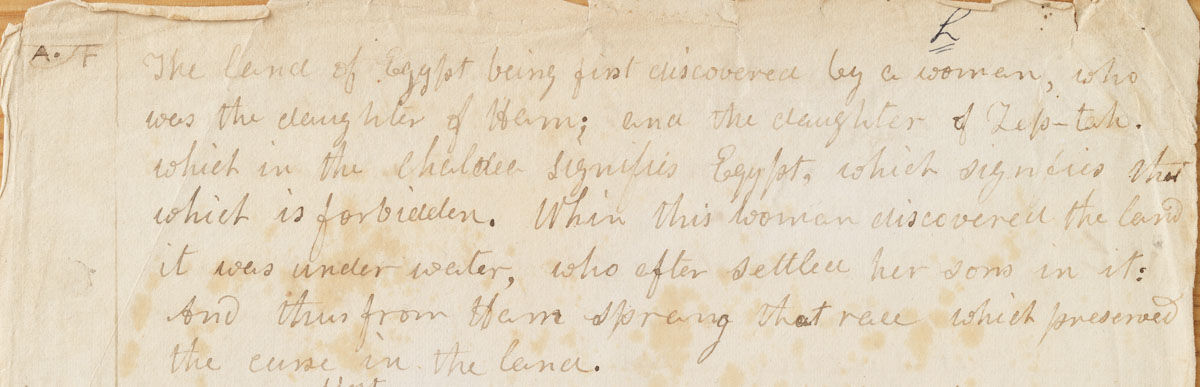

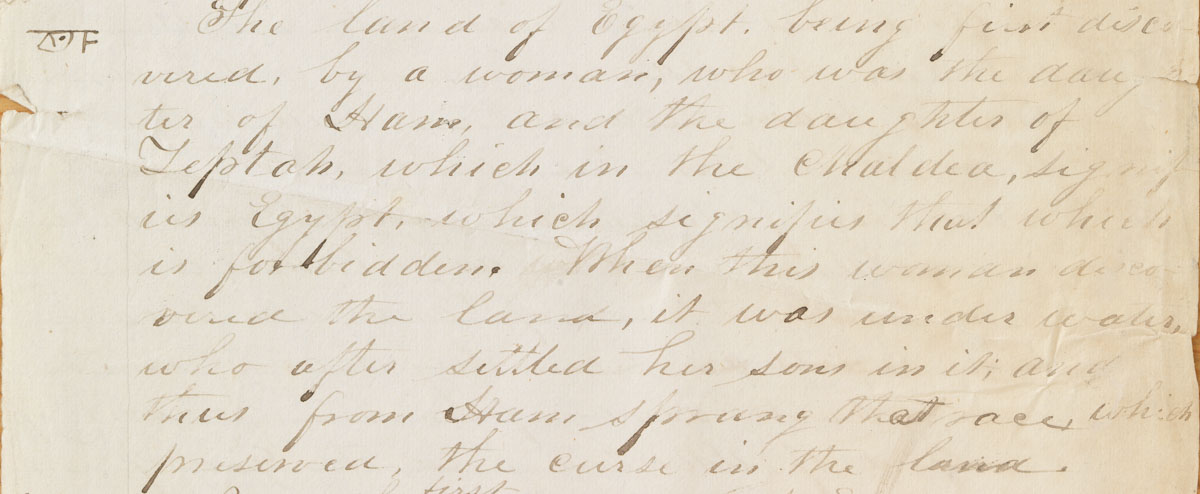

Figures 21 and 22. Top: “Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–A,” [3]. Bottom: “Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–B,” 4. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The name “Zep-tah” or “Zeptah” is visible on the second line from the top of Book of Abraham Manuscript–A and on the fourth line of the second full paragraph in the middle of Book of Abraham Manuscript–B.

Figures 21 and 22. Top: “Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–A,” [3]. Bottom: “Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa July–circa November 1835–B,” 4. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The name “Zep-tah” or “Zeptah” is visible on the second line from the top of Book of Abraham Manuscript–A and on the fourth line of the second full paragraph in the middle of Book of Abraham Manuscript–B.