Notes

Thank you so much to my dear sons Donnie and Nicholas Bradley for supporting and inspiring this work and for the love they have given across their lives. I also wish to acknowledge Jack Welch, John Thompson, Alex Criddle, and Jonathan Neville for their suggestions on this paper.

- 1. “History, Circa Summer 1832,” in Histories, Volume 1: Joseph Smith Histories, 1832–1844, ed. Karen Lynn Davidson, David J. Whittaker, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, Joseph Smith Papers (Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 15–16, 16n61; and “Preface to Book of Mormon, circa August 1829,” in Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831, ed. Michael Hubbard MacKay, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, Joseph Smith Papers (Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 92–94.

- 2. Book of Mormon, 1830 edition, “Preface to the Reader,” iii–iv.

- 3. See “Seer Stone,” Glossary, The Joseph Smith Papers, Church Historian’s Press, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/topic/seer-stone; “History, 1834–1836,” in Davidson and others, eds., Histories, Volume 1, 41; and “Volume 1 Introduction: Joseph Smith Documents Dating Through June 1831,” in MacKay and others, eds., Documents, Volume 1, xxix–xxxii; See also Mosiah 8:13; 28:13; and Ether 4:5.

- 4. Joseph wrote, “Through the medium of the Urim and Thummim I translated the record by the gift, and power of God.” “‘Church History,’ 1 March 1842,” in Davidson and others, eds., Histories, Volume 1, 495; “Volume 1 Introduction,” xxix–xxx, xxxn27; See Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publication of the Book of Mormon (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2015), 119–30; Anthony Sweat, “By the Gift and Power of Art,” in MacKay and Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light, 229–43; and Stan Spencer, “What Did the Interpreters (Urim and Thummim) Look Like?,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 33 (2019): 223–56, https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/what-did-the-interpreters-urim-and-thummim-look-like/.

- 5. I am grateful for dialogue with Jonathan Neville on the evidence presented here from Mormon’s plates. See his Whatever Happened to the Golden Plates?, updated ed. (Digital Legend, 2023), Kindle ed. For a positive appraisal of Neville’s perspective, see Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates: A Cultural History (Oxford University Press, 2023), 172–73.

- 6. “Title Page of the Book of Mormon, circa Early June 1829,” in MacKay and others, eds., Documents, Volume 1, 63–65.

- 7. While “plates of Nephi” are mentioned on the title page, this refers to Nephi’s large plates, rather than the small plates—as shown by how these plates are described. The title page begins, “The Book of Mormon: an account written by the hand of Mormon upon plates taken from the plates of Nephi. Wherefore, it is an abridgment of the record of the people of Nephi.” Notably, this does not say that the plates of Nephi were spliced into Mormon’s plates; but, rather, that Mormon’s plates were “taken from” the plates of Nephi. The title page provides the context for what this means. It reasons that Mormon’s record being “taken from” the plates of Nephi makes it “an abridgment,” dovetailing with other texts that describe Mormon’s record as an abridgment from the large plates of Nephi (for example, W of M 1:3). Indeed, Mormon elsewhere uses the title page’s precise language to describe his process of abridging the large plates—“And now I, Mormon, proceed to finish out my record, which I take from the plates of Nephi” (W of M 1:9, emphasis added; compare v. 5)—implying that the “plates of Nephi” from which Mormon’s record was “taken” are the large plates. Another indication that the title page’s reference to the “plates of Nephi” does not describe the small plates is its identification of the record as “an account written by the hand of Mormon,” unlike the small plates of Nephi written by Nephi, Jacob, and others.

- 8. For Moroni as the author of all or part of the title page, see Sidney B. Sperry, “Moroni the Lonely: The Story of the Writing of the Title Page to the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4, no. 1 (1995): 255–59; and David B. Honey, “The Secular as Sacred: The Historiography of the Title Page,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 3, no. 1 (1994): 94–103.

- 9. Mormon’s abridged material covers up through King Benjamin (W of M 1:3), so it would have covered from 600 BC to around 130 BC, a historical span of about 470 years. Regarding the lost manuscript, see Don Bradley, The Lost 116 Pages: Reconstructing the Book of Mormon’s Missing Stories (Greg Kofford Books, 2019).

- 10. One might propose that Moroni attached the small plates to Mormon’s record only after composing the title page, but this view is problematic. The only source that can be read as suggesting the two sets of plates were bound together attributes the act to Mormon, not Moroni, and places it before Moroni received either set of plates (W of M 1:6). Also, Moroni reveals in Moroni 1:1 that he considered the record complete after adding the book of Ether—“Now I, Moroni, after having made an end of abridging the account of the people of Jared, I had supposed not to have written more”—so a title page mentioning the book of Ether should reflect his complete intended work. If it is nevertheless supposed that Moroni added the small plates after the book of Ether, then he could have also added mention of these plates on the title page, leaving the problem of his omission of the small plates from the title page still unresolved.

- 11. Based on the 2013 English edition of the Book of Mormon and adjusting for the commentary from Moroni, the book of Ether comprises about 30 pages, which is approximately 5.65 percent (30 pages divided by 531 pages). The small plates of Nephi (1 Nephi–Omni, 143 pages) comprise 26.9 percent. Similar ratios can be calculated using digital word counts.

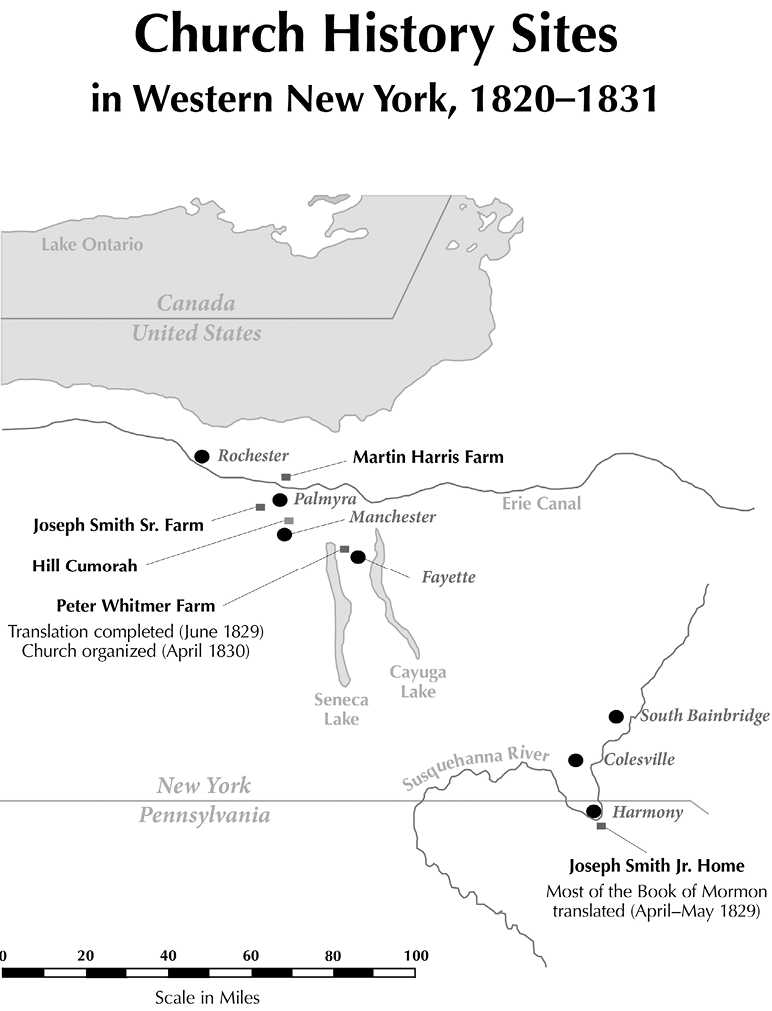

- 12. I use the term “Hill Cumorah” here as the traditional designation for the hill where Joseph Smith found the plates. How this hill relates to the hill called Cumorah in the Book of Mormon text is an open question to be addressed by other authors. See, for instance, Andrew H. Hedges, “Book of Mormon Geographies,” BYU Studies Quarterly 60, no. 3 (2021): 196–200.

- 13. Examples of this assumption can be found widely across time in Latter-day Saint discourse on the Book of Mormon. See, for example, B. H. Roberts, An Analysis of the Book of Mormon: Suggestions to the Reader (Millennial Star Office, 1888), 3, https://scripturecentral.org/archive/books/book/analysis-book-mormon-suggestions-reader?searchId=0eb3e36bfb24dcd9bb1d1bece1531216b59539a8fde17ee80224af0653c92aa3-en-v=e261582; John A. Tvedtnes, “Composition and History of the Book of Mormon,” New Era, September 1974, 41–43, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/new-era/1974/09/composition-and-history-of-the-book-of-mormon; Eldin Ricks, “The Formation of the Book of Mormon Plates,” Improvement Era, November 1960, 796–97, 852–54, https://archive.org/details/improvementera6311unse/mode/2up; and Grant R. Hardy, “Book of Mormon Plates and Records,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, vol. 1, A–D (Macmillan, 1992), https://eom.byu.edu/index.php?title=Book_of_Mormon_Plates_and_Records.

- 14. American Dictionary of the English Language, under “put,” Websters Dictionary 1828, accessed August 31, 2025, https://webstersdictionary1828.com/Dictionary/put.

- 15. For descriptions of the stack of plates being bound together by rings see documents 97, 107, and 146 in “Documents of the Translation of the Book of Mormon,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820–1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2d. ed. (Brigham Young University Press; Deseret Book, 2017), 175, 181, 202.

- 16. Joseph reported that “the Title Page of the Book of Mormon is a literal translation taken from the very last leaf, on the left hand side of the collection or book of plates, which contained the record which has been translated.” “History Drafts, 1838–Circa 1841,” in Davidson and others, eds., Histories, Volume 1, 352. This suggests that the title page may have been the final portion of Mormon’s plates that Joseph translated before (as described below) returning the plates in May 1829 to the messenger who had delivered them. Such data points regarding the structure of the plates support the view that Nephi’s small plates were bound separately from Mormon’s plates. Various scholars have concluded that the evidence makes it implausible for Nephi’s small plates to have had a position within Mormon’s plate stack. While the author interned with the Joseph Smith Papers Project working with the 1820s sources, Michael Hubbard Mackay and other scholars examined the evidence for the placement of the small plates in Mormon’s record and found no placement consistent with the evidence. Latter-day Saint scholars Terryl and Nathaniel Givens similarly assessed the evidence for where the plates of Nephi could fit in Mormon’s plate stack and “gave up not because it was indeterminate but because no location at all made sense.” Nathaniel Givens, personal communication to author, February 9, 2021.

- 17. For the small plates being translated after Mormon’s plates, see J. B. Haws, “The Lost 116 Pages Story: What We Do Know,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, ed. Dennis L. Largey, Andrew H. Hedges, John Hilton III, and Kerry Hull (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2015), 90–92; Brent Lee Metcalfe, “The Priority of Mosiah: A Prelude to Book of Mormon Exegesis,” in New Approaches to the Book of Mormon: Explorations in Critical Methodology¸ ed. Brent Lee Metcalfe (Signature Books, 1993), 395–444; and Royal Skousen, “Critical Methodology and the Text of the Book of Mormon,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 6, no. 1 (1994): 121–44.

- 18. “Revelation, May 1829–A [D&C 11],” and “Revelation, May 1829–B [D&C 12],” in MacKay and others, Documents, Volume 1, 50–57.

- 19. John W. Welch, “Timing the Translation of the Book of Mormon: ‘Days [and Hours] Never to Be Forgotten,’” BYU Studies Quarterly 57, no. 4 (2018): 10–50; Patrick A. Bishop, Day After Day: The Translation of the Book of Mormon (Eborn Publishing, 2018); Elden J. Watson, “Approximate Book of Mormon Translation Timeline,” April 1995, http://www.eldenwatson.net/BoM.htm; Dan Vogel, Joseph Smith: the Making of a Prophet (Signature Books, 2004), 363.

- 20. Welch, “Timing the Translation of the Book of Mormon,” 35.

- 21. The original manuscript of the Book of Mormon shows a shift of handwriting to another scribe, initially identified by Royal Skousen as an anonymous “Scribe 2,” in the original chapter 1 of First Nephi, at what is now 1 Nephi 3:7. Royal Skousen, ed., The Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon: Typographical Facsimile of the Extant Text (Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2001), 14. Skousen has subsequently identified this “Scribe 2” as John Whitmer. Royal Skousen, “The History of the Book of Mormon Text: Parts 5 and 6 of Volume 3 of the Critical Text,” BYU Studies Quarterly 59, no. 1 (2020): 115. Joseph Smith noted that “John Whitmer, in particular, assisted us very much in writing during the remainder of the work” of translation at the Whitmer residence. “History Drafts, 1838–Circa 1841,” 308.

- 22. “David Whitmer Interview with Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith, 7–8 September 1878,” in Early Mormon Documents, comp. and ed. Dan Vogel, 5 vols. (Signature Books, 1996–2003), 5:51–52, reproduced from “Report of Elders Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith,” Deseret News, November 16, 1878.

- 23. Edward Stevenson, Journal, February 9, 1886, 24:34–36 [image 38–40], Edward Stevenson Collection 1849–1922, Church History Catalog, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://catalog.churchofjesuschrist.org/assets/9f4720e3-45cf-4f74-8e7c-94374708b5e4/0/39.

- 24. “History Drafts, 1838–Circa 1841,” 236–38, emphasis added. See also Joseph Smith—History 1:59–60.

- 25. “Martin Harris Interview with Joel Tiffany, January 1859,” in Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 2:310, reproduced from “Mormonism–No. II,” Tiffany’s Monthly: Devoted to the Investigation of the Science of Mind, in the Physical, Intellectual, Moral and Religious Planes Thereof 5, no. 4 (August 1859): 170.

- 26. Orson Pratt, A Interesting Account of Several Remarkable Visions, and of the Late Discovery of Ancient American Records (Edinburgh, 1840), 13–14, https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/NCMP1820-1846/id/2821.

- 27. “History Drafts, 1838–Circa 1841,” 238. Compare Joseph Smith—History 1:60.

- 28. Another explanation that could be offered for Joseph and Oliver relocating to the Whitmer home at the end of May 1829, albeit one that does not account for them doing so upon completing the plates of Mormon, is the idea that the Whitmers had initiated this relocation by offering their home for the remainder of the translation. However, David Whitmer stated emphatically that the initiative for the relocation came from Joseph, who requested the Whitmers to open up their home: “Soon after I received another letter from Cowdery, telling me to come down into Pennsylvania and bring him and Joseph to my father’s house, giving me a reason therefor that they had received a commandment from God to that effect.” David Whitmer, “Mormonism,” Kansas City Journal, June 5, 1881, https://catalog.churchofjesuschrist.org/assets/daac9a1e-5938-4487-9610-0e4e5b5981ed/0/0. Similarly, persecution in Harmony may be cited as a reason for the relocation. Although Joseph’s reminiscent history of this early period mentions persecution around the time of his and Oliver’s encounter with John the Baptist on May 15, 1829, he does not give this as a reason for their subsequent relocation to Fayette. It seems likely that Joseph mistakenly placed this persecution in 1829 when it actually belonged in 1828. Joseph’s recollection describes Emma’s father’s family (Hales) but not her mother’s family (Lewis) as a bulwark against this persecution. This suggests that some of the persecution occurred in the summer of 1828, when the Lewises managed to get Joseph expelled from the Methodist probationary class and threatened to have him investigated on the charge of being “a practicing necromancer.” “Joseph and Hiel Lewis Statements, 1879,” in Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 4:311, reproducing Joseph Lewis, “Review of Mormonism. Rejoinder to Elder Cadwell,” Amboy (Ill.) Journal, June 11, 1879, 1. Despite such evidence for 1828 persecutions against Joseph in Harmony, no extant evidence indicates that there were persecutions against him there in 1829. There is also no evidence that Joseph and Oliver slackened their pace of translation in April–May 1829 while at Harmony. In fact, Joseph did his most rapid translation work at precisely this time. See Bradley, Lost 116 Pages, 97–101.

- 29. Joseph Smith never explained how he acquired the small plates, perhaps in line with his 1831 statement that “it was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the book of Mormon, & also said that it was not expedient for him to relate these things.” “Volume 1 Introduction,” xxix.

- 30. See Cameron J. Packer, “Cumorah’s Cave,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 13, no. 1–2 (2004): 50–57.

- 31. Stevenson, Journal, December 23, 1877, 14:18 [image 24]. According to David Whitmer’s account, “My mother was going to milk the cows, when she was met out near the yard by the same old man (judging by her description of him) who said to her, ‘You have been very faithful and diligent in your labors, but you are tired because of the increase of your toil, it is proper therefore that you should receive a witness that your faith may be strengthened.’ Thereupon he showed her the plates.” “David Whitmer Interview with Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith,” in Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 5:51–52; Royal Skousen, “Another Account of Mary Whitmer’s Viewing of the Golden Plates,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 10 (2014): 36; Amy Easton-Flake and Rachel Cope, “A Multiplicity of Witnesses: Women and the Translation Process,” in Largey and others, Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon, 133–36.

- 32. While it would make the most sense for the messenger to bring to the Whitmer farm the plates Joseph had not yet translated—the small plates, the messenger may have brought both sets of plates. One nineteenth-century Utah Latter-day Saint, after hearing the story of Mary Whitmer from David Whitmer, understood that the plates the angel showed her were Mormon’s plates. Edward Stevenson, who heard David Whitmer relate Mary Whitmer’s report in 1877, 1886, and 1887, wrote in his 1886 journal entry after his second Whitmer interview that the angel had shown Mary Whitmer a set of plates that were partly sealed, which, if accurate, would presumably have been the plates of Mormon. The assertion that Mary Whitmer saw the sealed plates is absent from Stevenson’s account of his earlier 1877 interview from the more detailed interview report by Joseph F. Smith and Orson Pratt that same year, and from all other reports of Mary Whitmer’s experience. Stevenson may have confused David Whitmer’s account of his mother’s experience of the plates with David’s own oft-repeated description of the plates as partly sealed based on his own experience of them as one of the Three Witnesses. “Edward Stevenson Interview, Diary, December 22–23, 1877,” in David Whitmer Interviews: A Restoration Witness, ed. Lyndon W. Cook (Grandin Book, 1991), 13; “David Whitmer Interview with Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith,” in Vogel, Early Mormon Documents, 5:51–52; “Edward Stevenson Interview, Diary, February 9, 1886,” in Cook, David Whitmer Interviews, 181–82; and E. Stevenson, “A Visit to David Whitmer,” Juvenile Instructor 22, no. 4 (February 15, 1887): 55.

- 33. That Nephi was involved at some point in the reception or transportation of plates is suggested by Joseph Smith’s conflation of Nephi and Moroni in the earliest draft of his 1838 History. “History Drafts, 1838–Circa 1841,” 222. (See also discussion of this variant in “History Drafts, 1838–Circa 1841,” 223n56.) Were Nephi not involved in some such way, it is difficult to understand why both Mary Whitmer and the Prophet Joseph employed the name Nephi as that of a messenger involved in the coming forth of the book of plates.

- 34. Easton-Flake and Cope, “Multiplicity of Witnesses,” 133–53.

- 35. Mary Magdalene’s role in testifying of the resurrected Christ to the Twelve garnered for her in early Christianity the designation of “apostle to the apostles.” See Brendan McConvery, “Hippolytus’ Commentary on the Song of Songs and John 20: Intertextual Reading in Early Christianity,” Irish Theological Quarterly 71, no. 3–4 (2006): 211–22, for an example of this from early in the second century.

- 36. For an insightful discussion of the neglect of women’s roles in the Book of Mormon’s emergence and an attempt to recover some of those roles, see Amy Easton-Flake and Rachel Cope, “Reconfiguring the Archive: Women and the Social Production of the Book of Mormon,” in Producing Ancient Scripture: Joseph Smith’s Translation Projects in the Development of Mormon Christianity, ed. Michael Hubbard MacKay, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Brian M. Hauglid (University of Utah Press, 2020), 105–34. Where published work on the coming forth of the Book of Mormon has acknowledged the roles played by others, including Mary Whitmer, these have almost always tended to be in the form of acknowledging their temporal assistance in the work, such as keeping Joseph with lodging and provisions while he translated. A salutary new trend toward greater acknowledgment of women’s roles in the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, including their roles as informal witnesses, may be found in several recent articles from Scripture Central, including “How Did Emma Smith Help Bring Forth the Book of Mormon?,” Scripture Central, KnoWhy #386, August 21, 2019, https://scripturecentral.org/knowhy/how-did-emma-smith-help-bring-forth-the-book-of-mormon?searchId=b99055ddcb9769a6e5f3f41f86110ed7a28ca06baa2f5660c8e73da305646ff1-en-v=e261582; “What Does Mary Whitmer Teach Us About Enduring Trials?,” Scripture Central, KnoWhy #455, August 21, 2019, http://scripturecentral.org/knowhy/what-does-mary-whitmer-teach-us-about-enduring-trials?searchId=b99055ddcb9769a6e5f3f41f86110ed7a28ca06baa2f5660c8e73da305646ff1-en-v=e261582; and Chris Heimerdinger, “5 Women Who Are Witnesses of the Physical Golden Plates,” Scripture Central, March 2, 2018, https://scripturecentral.org/blog/5-women-who-are-witnesses-of-the-physical-golden-plates?searchId=b99055ddcb9769a6e5f3f41f86110ed7a28ca06baa2f5660c8e73da305646ff1-en-v=e261582.

- 37. The Prophet Joseph Smith has unquestionably been the central instrument in God’s hands to inaugurate the work of restoration. Yet, as President Russell M. Nelson has taught, the Restoration was not a one-time work, either by Joseph or anyone else; rather, it is an ongoing process in which we participate. Russell M. Nelson, “Hear Him,” Liahona, May 2020, 88. For example, Martin Harris received a vision, as stated by Joseph in his 1832 history: “a man by the name of Martin Har[r]is . . . became convinced of th[e] vision and . . . the Lord appeared unto him in a vision and shewed unto him his marvilous work which he was about to do and <h[e]> imediately came to Suquehannah and said the Lord had shown him that he must go to new York City <with> some of the characters so we proceeded to coppy some of them and he took his Journy to the Eastern Cittys and to the Learned.” “History, circa Summer 1832,” in Davidson and others, Histories, Volume 1, 15. See also Welch, Opening the Heavens.