Notes

1. John Gee, “Eyewitness, Hearsay, and Physical Evidence of the Joseph Smith Papyri,” in The Disciple as Witness: Essays on Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson, ed. Stephen D. Ricks, Donald W. Parry, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2000), 186.

2. On the conflicting Egyptological opinions, see Friedrich Freiherr von Bissing, in F. S. Spalding, Joseph Smith, Jr., as a Translator (Salt Lake City: Arrow Press, [1912]), 30; and George R. Hughes, quoted in Hugh Nibley, An Approach to the Book of Abraham, ed. John Gee, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 18 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2009), 144, who saw nothing inordinate with figure 3 holding a knife; but contrast with Klaus Baer, “The Breathing Permit of Hôr: A Translation of the Apparent Source of the Book of Abraham,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 3, no. 3 (Autumn 1968): 118 n. 34; Stephen E. Thompson, “Egyptology and the Book of Abraham,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 28, no. 1 (1995): 148–49; and Lanny Bell, “The Ancient Egyptian ‘Books of Breathing,’ the Mormon ‘Book of Abraham,’ and the Development of Egyptology in America,” in Egypt and Beyond: Essays Presented to Leonard H. Lesko upon His Retirement from the Wilbour Chair of Egyptology at Brown University June 2005, ed. Stephen E. Thompson and Peter der Manuelian (Providence, R.I.: Brown University Press, 2008), 25 nn. 27, 30.

3. William I. Appleby, Journal, May 5, 1841, 72, MS 1401, Church History Library; reprinted in Brian M. Hauglid, ed., A Textual History of the Book of Abraham: Manuscripts and Editions (Provo, Utah: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2010), 279. That this source indeed dates to 1841 and is not just a later retrospective can be determined by the publication of excerpts of Appleby’s journal in a contemporary newspaper. See “Journal of a Mormon,” Christian Observer 20, no. 37 (September 10, 1841): 146.

4. Henry Caswall, The City of the Mormons; or, Three Days at Nauvoo, in 1842 (London: Rivington, 1842), 23.

5. Gee, “Eyewitness, Hearsay, and Physical Evidence,” 186.

6. Gee, “Eyewitness, Hearsay, and Physical Evidence,” 208 n. 38.

7. Robert Kriech Ritner, The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice (Chicago: Oriental Institute, 1993), 163, see additionally 163–67; Marquardt Lund, “Egyptian Depictions of Flintknapping from the Old and Middle Kingdom, in Light of Experiments and Experience,” in Egyptology in the Present: Experiential and Experimental Methods in Archaeology, ed. Carolyn Graves-Brown (Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, 2015), 113–37; Carolyn Graves-Brown, “Flint and Forts: The Role of Flint in Late Middle-New Kingdom Egyptian Weaponry,” in Walls of the Prince: Egyptian Interactions with Southwest Asia in Antiquity: Essays in Honour of John S. Holladay, Jr., ed. Timothy P. Harrison, Edward B. Banning, and Stanley Klassen (Leiden, Neth.: Brill, 2015), 37–59; William M. Flinders Petrie, Illahun, Kahun and Gurob: 1889–1890 (London: David Nutt, 1891) 52–53, plate VII; f. Ll. Griffith, Beni Hasan, Part III (London: Egypt Exploration Fund, 1896), 33–38, plates VII–X.

8. Carolyn Anne Graves-Brown, “The Ideological Significance of Flint in Dynastic Egypt” (PhD diss., University College London, 2010), 1:278; compare Kerry Muhlestein, Violence in the Service of Order: The Religious Framework for Sanctioned Killing in Ancient Egypt (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011), esp. 18–20, 37–41.

9. Graves-Brown, “Ideological Significance of Flint,” 1:144–45, 208, 223, 242–44, 271–73; Christina Riggs, Unwrapping Ancient Egypt (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 91–92; R. L. Vos, The Apis Embalming Ritual: P. Vindob. 3873 (Leuven: Peeters, 1993), 195 n. 110.

10. Théodule Devéria, in Remy, Voyage au pays des Mormons, 2:463; Devéria in Remy and Brenchley, Journey to the Great-Salt-Lake City, 2:540; Bell, “Ancient Egyptian ‘Books of Breathing,’” 30.

11. James H. Breasted, Friedrich Freiherr von Bissing, and Edward Meyer in Spalding, Joseph Smith, Jr., as a Translator, 26, 30; George R. Hughes, in Nibley, Approach to the Book of Abraham, 144; John Gee, “Abracadabra, Isaac, and Jacob,” FARMS Review of Books 7, no. 1 (1995): 80–83; Nibley, Approach to the Book of Abraham, 34, 288, 494–95.

12. Devéria, in Jules Remy, Voyage au pays des Mormons, 2:463; Devéria in Remy and Brenchley, Journey to the Great-Salt-Lake City, 2:540; William Flinders Petrie in Spalding, Joseph Smith, Jr., as a Translator, 23; Baer, “Breathing Permit of Hôr,” 118; Thompson, “Egyptology and the Book of Abraham,” 144; Rhodes, Hor Book of Breathings, 18; Bell, “Ancient Egyptian ‘Books of Breathing,’” 23.

13. Rhodes, Hor Book of Breathings, 18.

14. There appears to have been one hieroglyphic caption above the arm of figure 3 in the original vignette preserved in Facsimile 1, but it is too damaged to read.

15. As noted in Gee, “Eyewitness, Hearsay, and Physical Evidence of the Joseph Smith Papyri,” 208 n. 38, the figure could potentially be the jackal-headed god Isdes (who, incidentally, wields a knife). See Christian Leitz, Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen (Leuven: Peeters, 2002), 1:560–61; and, additionally, Diletta D’antoni, Il Dio Isdes (BA thesis, University of Bologna, 2014), 8–9, on the identity of the god Isdes as judge and punisher of the dead.

16. Penelope Wilson, “Masking and Multiple Personas,” in Ancient Egyptian Demonology: Studies on the Boundaries between the Demonic and the Divine in Egyptian Magic, ed. P. Kousoulis (Leuven: Peeters, 2011), 77.

17. Ritner, Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice, 249 n. 1142; compare Wilson, “Masking and Multiple Personas,” 78–79; and Carolyn Graves-Brown, Daemons and Spirits in Ancient Egypt (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2018), 54–55.

18. Alexandra von Lieven, “Book of the Dead, Book of the Living: BD Spells as Temple Texts,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 98 (2012): 263.

19. Robert K. Ritner, “Osiris-Canopus and Bes at Herculaneum,” in Joyful in Thebes: Egyptological Studies in Honor of Betsy M. Bryan, ed. Richard Jasnow and Kathlyn M. Cooney (Atlanta: Lockwood Press, 2015), 401.

20. Ritner, “Osiris-Canopus and Bes at Herculaneum,” 406; compare Wilson, “Masking and Multiple Personas,” 79–82, who discusses the use of masks in ritual and role playing and what that may have signified to the ancient Egyptians.

21. See further Terence DuQuesne, “Concealing and Revealing: The Problem of Ritual Masking in Ancient Egypt,” Discussions in Egyptology 51 (2001): 5–31, esp. 14–19.

22. Gee, “Abracadabra, Isaac, and Jacob,” 80–83, citations removed, emphasis in original; compare Gee, Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri, 36–39; Michael D. Rhodes, “Teaching the Book of Abraham Facsimiles,” Religious Educator 4, no. 2 (2003): 120; Nibley, Approach to the Book of Abraham, 34, 288, 494–95; Günther Roeder, Die Denkmäler des Pelizaeus-Museums zu Hildesheim (Hildesheim: Karl Curtius Verlag, 1921), 127, plate 49; and Deborah Sweeney, “Egyptian Masks in Motion,” Göttinger Miszellen 135 (1993): 101–4. See additionally the recent study of Barbara Richter, “Gods, Priests, and Bald Men: A New Look at Book of the Dead 103 (‘Being Besides Hathor’),” in The Book of the Dead, Saite through Ptolemaic Periods: Essays on Books of the Dead and Related Topics, ed. Malcolm Mosher Jr. (Prescott, Ariz.: SPBDStudies, 2019), 519–40, who discusses the polyvalence of the terms iAs and iHy as they apply to the Egyptian priesthood of Ihy/Hathor. “The word iAs can refer to the baldness of all Egyptian priests, but it can also recall the intermediary statues of the ‘bald ones of Hathor,’ who relay the words of the goddess. The word iHy can indicate the god, who offers the deceased protection, renewal, and rejuvenation, but it can also refer to the iHy-priests, whose feather headdresses in the determinatives emphasize their roles in music and dancing—a necessity for pacifying Hathor’s dangerous side.” Richter, “Gods, Priests, and Bald Men,” 535.

23. Emily Teeter, Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 24–25.

24. P. Jumilhac 13/14–14/4, in Jacques Vandier, Le Papyrus Jumilhac (Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1962), 125–26.

25. Gee, Guide to the Joseph Smith Papyri, 39.

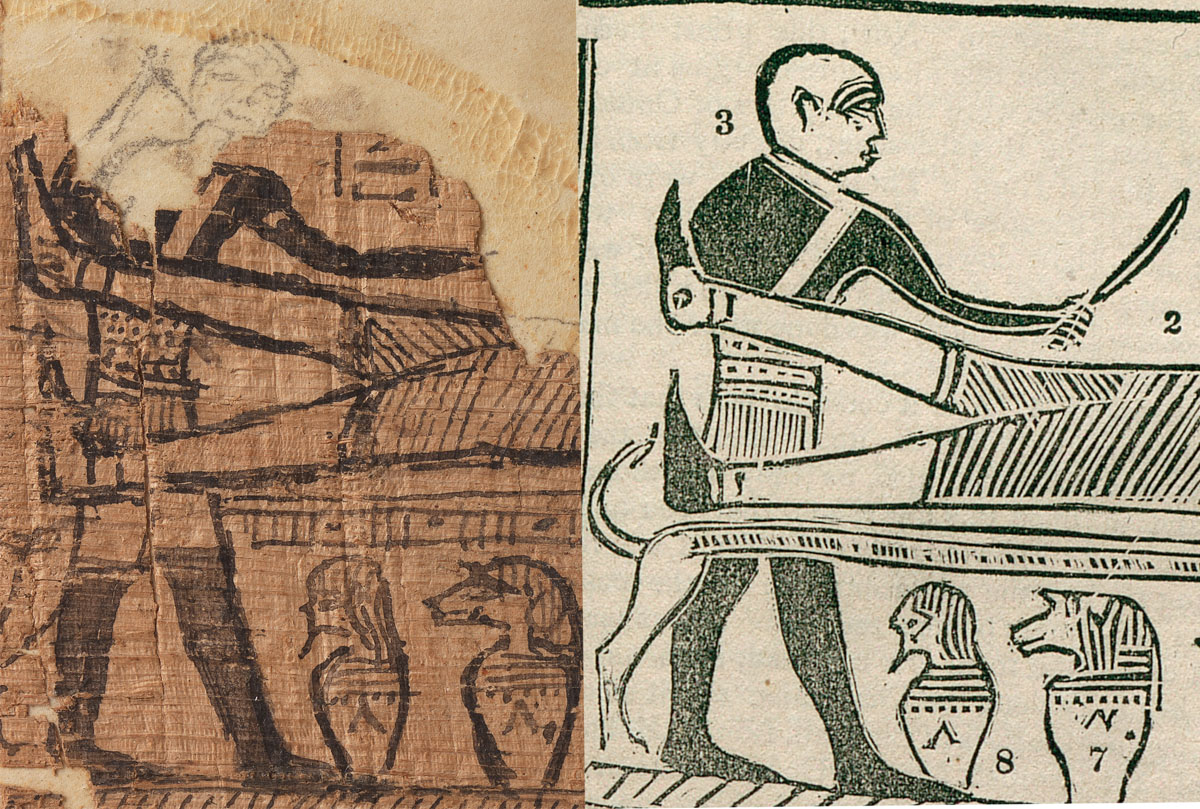

Figure 30. A side-by-side comparison of figure 3 in Facsimile 1, as published by Joseph Smith in 1842 (right), and the original papyrus fragment (left). © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

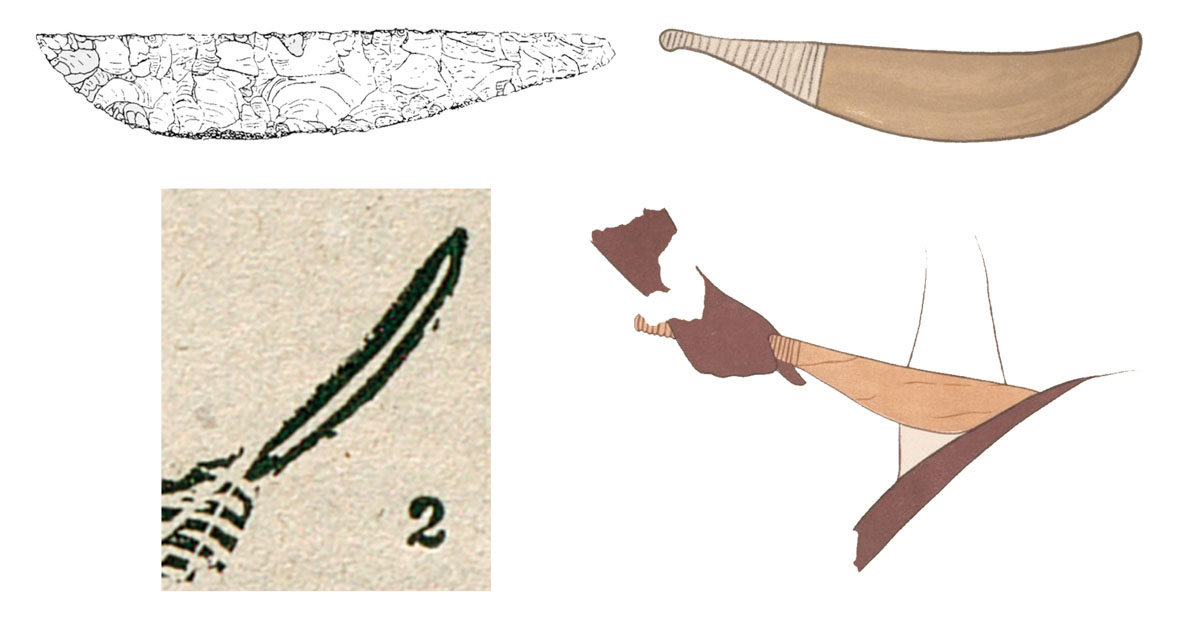

Figure 30. A side-by-side comparison of figure 3 in Facsimile 1, as published by Joseph Smith in 1842 (right), and the original papyrus fragment (left). © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Figure 31. The knife in Facsimile 1 (bottom left) is consistent in shape with recovered flint knives (top left) and depictions of flint knives (top right, bottom right) from the Middle Kingdom. Images starting at top left and running clockwise: Petrie (1891), plate VII; Griffith (1896), plate VIII; Griffith (1896), plate IX; © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Figure 31. The knife in Facsimile 1 (bottom left) is consistent in shape with recovered flint knives (top left) and depictions of flint knives (top right, bottom right) from the Middle Kingdom. Images starting at top left and running clockwise: Petrie (1891), plate VII; Griffith (1896), plate VIII; Griffith (1896), plate IX; © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Figure 32. The faint remaining traces of what seems to have been a jackal headdress appear over the shoulder of figure 3 of Facsimile 1. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Figure 32. The faint remaining traces of what seems to have been a jackal headdress appear over the shoulder of figure 3 of Facsimile 1. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.