Notes

1. See the case made in Quinten Barney, “Sobek: The Idolatrous God of Pharaoh Amenemhet III,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 2 (2013): 22–27.

2. Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 200; Marco Zecchi, Sobek of Shedet: The Crocodile God in the Fayyum in the Dynastic Period, Studi Sull’antico Egitto 2 (Todi, It.: Tau Editrice, 2010); and Tine Bagh, “Sobek Crowned,” in Lotus and Laurel: Studies on Egyptian Language and Religion in Honour of Paul John Frandsen, ed. Rune Nyord and Kim Ryholt (Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2015), 1–17.

3. Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 218–19.

4. Hermann Ranke, Die Ägyptischen Personennamen (Glückstadt, Ger.: Verlag von J. J. Augustin, 1935), 1:303–6.

5. Ronald J. Leprohon, The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 60–61, 64, 67–68, 70.

6. Wilkinson, Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, 220.

7. Beatrice Teissier, Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Middle Bronze Age (Fribourg, Switz.: University Press Fribourg Switzerland, 1996), 10 n. 34; Gabriella Scandone Matthiae, “The Relations between Ebla and Egypt,” in The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer D. Oren (Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, 1997), 421–22; Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, and Jean M. Evans, eds., Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008), 37; Kerry Muhlestein, “Levantine Thinking in Egypt,” in Egypt, Canaan, and Israel: History, Imperialism, Ideology and Literature, ed. S. Bar, D. Kahn, and J. J. Shirley (Leiden, Neth.: Brill, 2011), 194; Paolo Matthiae, “Elba: Recent Excavation Results and the Continuity of Syrian Art,” in Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C., ed. Joan Aruz, Sarah B. Graff, and Yelena Rakic (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), 109–10. Note also the important comment in Anna-Latifa Mourad, Rise of the Hyksos: Egypt and the Levant from the Middle Kingdom to the Early Second Intermediate Period (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2015), 173: “Two additional antithetic [ivory] fragments [discovered at Ebla] represent a falcon-headed figure, whereas another inlay preserves the full body of a crocodile-headed individual. . . . Such Egyptian elements are manifestations of royalty and divinity. The Levantine artist(s) who crafted the inlays was thereby well-versed in Egyptian symbolism and art. The choice to pair the inlays with a piece of palatial furniture further highlights the association of Egyptian art with Eblaite elitism and power.”

8. Tine Bagh, “Sobek Crowned,” 1; compare Zecchi, Sobek of Shedet, 21–106, esp. 37–53.

9. Zecchi, Sobek of Shedet, 41.

10. Barney, “Sobek,” 26, modifying the translation provided in Alan Gardiner, “Hymns to Sobk in a Ramesseum Papyrus,” Revue d’Égyptologie 11, no. 2 (1957): 43–56, quote at 48.

11. Zecchi, Sobek of Shedet, 47, reviewing Middle Kingdom evidence, observes how “in the Middle Kingdom, in the Fayyum, Sobek’s duties were manifold; he exercised control over the whole world, from the waters to the sky, but he was essentially a god who had become Horus and, as such, connected with royal doctrines. The image of the crocodile is . . . the shape that Horus himself adopts when entering the Fayyum. Moreover, the temple of Sobek became a centre for the recognition of the royal power. The syncretism between the two deities and the new group of epithets had a specific function. They not only increased the importance of the local—and provincial—crocodile-god, but they also served the king, who could receive the divine essence of kingship only from a god who was able to be strongly royal.”

12. One source contemporary to Joseph Smith did report that “the crocodile or hippopotamus” was “the emblem of Pharaoh and the Egyptians” and “was one of their principal divinities.” This source also reported that “Pharaoh . . . signifies a crocodile.” Adam Clarke, The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments, 6 vols. (London: Thomas Tegg and Son, 1836), 1:1901, 281. (This Bible edition with Clarke’s notes was based on an eight-volume commentary series Clarke published between 1810–1826.) By contrast, the Book of Abraham says nothing about hippopotami and indicates that “Pharaoh signifies king by royal blood” (Abr. 1:20), not “crocodile.” Furthermore, none of the archaeological or inscriptional evidence confirming Sobek’s presence in northern Syria or his association with Egyptian kingship was available in Joseph Smith’s lifetime.

13. See further Elizabeth Laney, “Sobek and the Double Crown,” The Ancient World: A Scholarly Journal for the Study of Antiquity 34 (2003): 155–68, esp. 158; Maryan Ragheb, “The Rise of Sobek in the Middle Kingdom,” American Research Center in Egypt, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.arce.org/resource/rise-sobek-middle-kingdom, emphasis in original: “It was Amenemhat III who brought the role of ‘Sobek of Shedet-Horus residing in Shedet’ to the highest significance. Sobek-Horus of Shedet became associated with epithets like ‘Lord of the wrrt (White) Crown,’ ‘he who resides in the great palace’ and ‘lord of the great palace.’ All of these epithets were related to the king rather than associated with any god. Even the name of Horus in this merged form was enclosed in a serekh like a king’s name. The king has always been identified as Horus on earth. With the new divine form of Sobek-Horus, the king as Horus merged with Sobek and incorporated himself as one with the god Sobek. Sobek’s association with divine kingship is illustrated in the Amenemhat III’s ‘Baptism of the Pharaoh’ scene at his Madinet Madi Temple in Fayum. This scene, the earliest of its kind, depicts Sobek and Anubis anointing Amenemhat III with ankh signs of life. The anointment marks the king’s initiation into eternal kingship and was usually related to the state god’s divine procreation of the king.”

14. John Gee, “The Crocodile God of Pharaoh in Mesopotamia,” Insights (October 1996): 2.

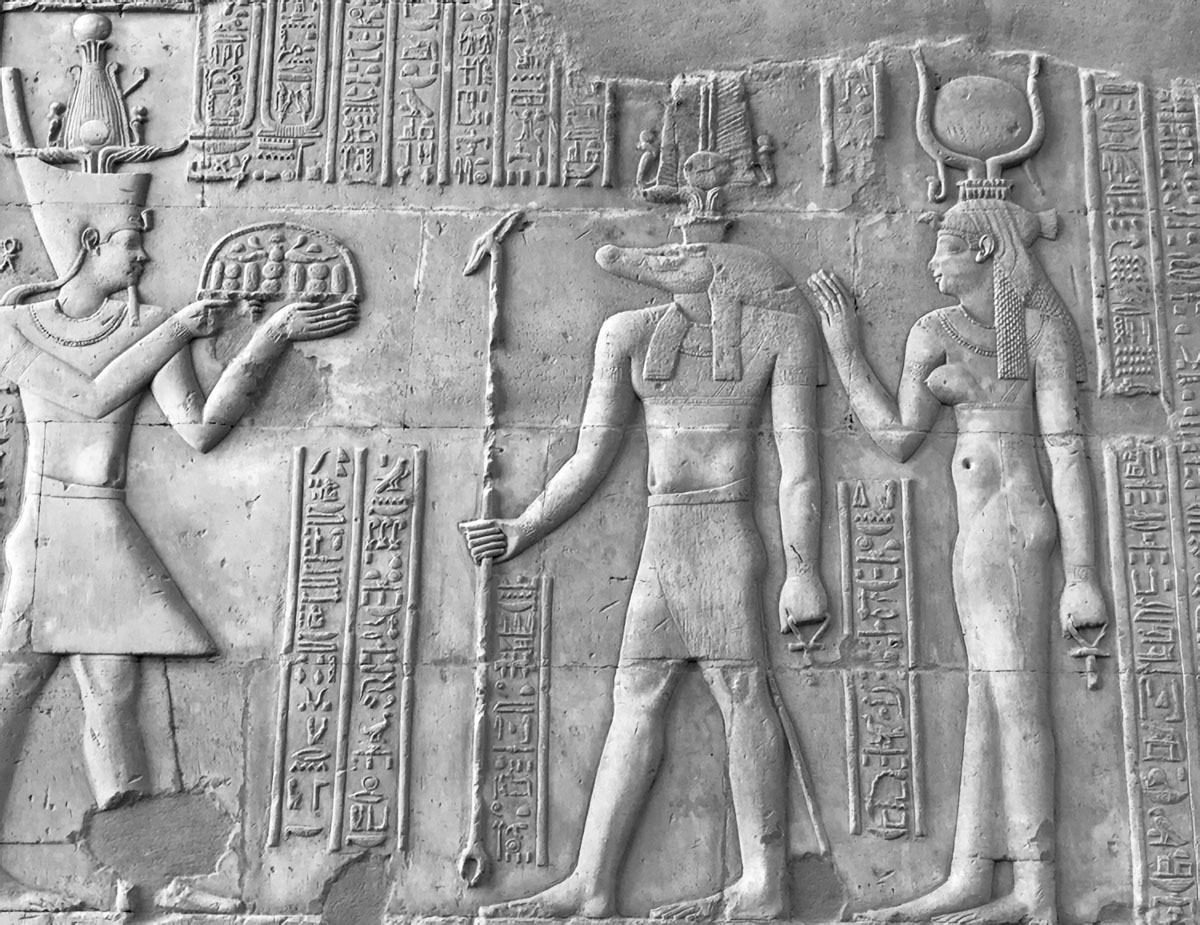

Figure 20. Relief at the temple of Kom Ombo depicting the god Sobek (middle). Photograph by Stephen O. Smoot.

Figure 20. Relief at the temple of Kom Ombo depicting the god Sobek (middle). Photograph by Stephen O. Smoot.