In recent years, both university and Church leaders have placed renewed and welcome emphasis on President Spencer W. Kimball’s “Second Century Address,” one of the central texts in the BYU canon. Of the many stirring ideas in that landmark address, one of the most evocative is President Kimball’s declaration that “gospel methodology, concepts, and insights can help us to do what the world cannot do in its own frame of reference.” Current BYU leaders have reflected on the concept of “gospel methodology,” and at the August 2022 university conference, Academic Vice President C. Shane Reese invited BYU faculty to explore “what gospel methodology might look like in [our] particular disciplinary context . . . [and] what concepts and insights [we] might incorporate into [our] personal teaching.”

We offer the following reflections as one response to that invitation. Our aim is to draw on gospel concepts and insights to provide a loose (not exhaustive) framework for considering components of a gospel methodology that apply to any teaching context regardless of discipline. These reflections are not intended as a precise prescription for practice but as underlying principles to ponder and as an invitation to think more openly and deeply about what it might mean to be consecrated in every act of teaching and learning at Brigham Young University.

Methodology as Motive and Means

We begin with a working definition, however tentative and incomplete, of gospel methodology. With respect to teaching, we suggest that gospel methodology encompasses both (1) the basic framework through which we view our subject, our students, and the fundamental purpose of our teaching and (2) the ways in which we teach. On this understanding, gospel methodology is about the why and the how of instruction—the motive and the means of education. We will have more to say about the second part of this formula later. For now, it is important to note, as AVP Reese observed in his university conference message, that the “how” of gospel methodology transcends mere technique (though technique is critically important) to encompass the Christian virtues that the teacher practices during the process of instruction.

The “motive” part of our formulation is, in a key sense, prepedagogical; it precedes any actual teaching. It encompasses the teacher’s entire outlook, purpose, and character. These elements must be in place before the teacher ever enters the classroom. They must inform everything that happens within the classroom.

Outlook. The essence of any methodology is an underlying principle or set of principles. The essence of gospel methodology is the set of principles comprised by the gospel of Jesus Christ, which is also known as the plan of salvation, the plan of redemption, and the plan of happiness. That plan is the fundamental prism and focal lens of gospel methodology. To employ gospel methodology is to view all things and all people in the context of our Father’s eternal plan. It is to view all people as children of God created in his image. It is to view each student as “a beloved spirit son or daughter of heavenly parents,” destined, if willing, to draw progressively closer to God and to become increasingly like him.

Motive. In addition to leading us to embrace God’s plan as our fundamental outlook, gospel methodology requires that we embrace God’s motive and purpose as our own. That motive is summarized in one of the most-cited of all scriptures: “For behold, this is my work and my glory—to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man” (Moses 1:39). This motive is entirely unselfish; it is utterly consumed with promoting others’ eternal advancement and blessing. To employ gospel methodology is to shed selfish motives and to promote the eternal flourishing of one’s students. It is to have “an eye single to the glory of God” (D&C 4:5), which entails both (1) promoting the immortality and eternal life of God’s children (Moses 1:39) and (2) pursuing “intelligence, or, in other words, light and truth” (D&C 93:36). Gospel methodology must rest, then, on obedience to the two great commandments: love of God and love of God’s children—inseparable, but in that order.

Character. This call to embrace selfless, Godlike motives points to the centrality of the teacher’s own character in the foundation of gospel methodology. Bitter fountains don’t yield pure water, and corrupt trees don’t produce good fruit. Gospel methodology can be employed only by a teacher who is striving to live the gospel. This doesn’t mean that teachers need to be perfect—that would reduce the teaching pool effectively to zero. But it does mean that we need to conscientiously cultivate a Christlike character.

The pure motive needed to ground a gospel methodology—what the revelations call “an eye single to the glory of God”—does not emerge in a vacuum, and it cannot stand alone. It develops in a virtuous, symbiotic cycle along with other Christlike attributes. Descriptions of those attributes are scattered throughout the scriptures, but succinct summaries are found in at least three crucial places: the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:1–12), the great revelation on missionary work (D&C 4), and the Prophet Joseph Smith’s letter from Liberty Jail (D&C 121:34–46). Collectively, these scriptures outline the constitution of a Christlike character. Such character, strengthened and solemnized by temple covenants, becomes the sine qua non of gospel methodology.

We believe that the kind of outlook, motive, and character just described is an essential condition for gospel methodology. But having dubbed that condition “prepedagogical,” we hasten to add that the necessary character refinement need not precede our actual teaching. Indeed, it cannot entirely precede teaching because much of the needed refinement comes through teaching. It comes as we practice in our teaching the virtues we need to acquire. Such practice forges the necessary link between the motive and the means of gospel methodology—between why we teach and how. Let us turn now to five principles or distinctions that provide gospel insight into how we teach.

1. Effective Teaching and Good Teaching

In his prophetic “Second Century” description of Brigham Young University’s future, President Kimball makes a clarion call for placing “heavy and primary emphasis . . . on the quality of teaching at BYU.” This petition for quality has multiple possible interpretations, but it forms a foundation for President Kimball’s subsequent invitation to employ a gospel methodology. An analysis of its root meaning suggests that for teaching to be of quality, it must be both effective and good—good in a moral/gospel sense. In other words, quality teaching must be successful in realizing its intended learning outcomes, but effectiveness is not enough. The nature of the subject matter cannot be dismissed, nor do successful outcomes (defined in terms of effectiveness) justify means that are incompatible with gospel principles.

For example, as faculty, we might be successful in teaching our students obscure facts with no relevant application (perhaps because the knowledge of those facts can be measured on a multiple-choice test), or we might find that shaming students in class for forgetting those obscure facts coerces other students to fearfully comply and demonstrate mastery of that information on a future exam. But neither of these examples of effective teaching constitute quality teaching because the subject matter (obscure facts) and the instructional methods (shaming) are morally indefensible. Thus quality teaching must be effective, but it also requires morally good content and morally good methods of instruction; quality teaching must be both effective and good in a moral/gospel sense.

For many faculty, the task to teach morally good subject matter is fairly straightforward. In the most direct way, that subject matter might be the gospel itself. However, it also includes the content of every discipline and course offering, so long as that content is good—true, correct, proper, right, decent, and so forth, as measured by the gospel of Jesus Christ. One way to enhance its goodness is to follow President Kimball’s admonition to teach every subject matter “bathed in the light and color of the restored gospel.” Such bathing can take many forms, including (but not limited to) seeking after relevant content that is “virtuous, lovely, or of good report or praiseworthy” (A of F 1:13); making connections (or distinctions) between secular theories and gospel truth; explaining key concepts (or challenging underlying assumptions) in relation to core doctrine; and providing gospel scaffolding to better understand disciplinary content.

The charge to keep our subject matter bathed in the light and color of the restored gospel receives further specification in the guardrails provided in the BYU Academic Freedom Policy, suggesting that anytime faculty discuss or analyze any secular position/theory that runs counter to key doctrine, it is necessary to take a faith-affirming stance in support of doctrine. It is not enough to present both sides of a controversial issue that conflicts with fundamental Church doctrine and leave students guessing as to the position of the faculty—even for the sake of discussion and analysis. To employ gospel methodology, we must bear witness of gospel truth. In these and other ways, faculty bathe their content in the light and color of the restored gospel.

2. Teaching Morality and Teaching Morally

Teaching the gospel as content (such as teaching one of the cornerstone courses in Religious Education) or bathing disciplinary content in the light and color of the restored gospel (such as presenting the theory of evolution in a biology course with reference to prophetic teachings about the plan of salvation) represent a necessary part of a gospel methodology. But morally good content, though necessary, is not sufficient. That content must be taught with morally good methods rooted in gospel principles. Put another way, we are only sometimes in a position to teach morality. But we are always in a situation to teach morally—to teach in ways that align with what is good, right, virtuous, and caring in a gospel sense. Teaching is a moral act. It is an inherently moral endeavor. And at BYU, every method and interaction must be informed by the principles and practices of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Certainly, these gospel principles and practices include prayer. Sincerely praying for guidance regarding what and how to teach is obviously crucial to gospel methodology. The same might be true of supplicating the heavens as a class to invite the Spirit to facilitate revelation and inspiration or of praying privately in behalf of our students. But teaching morally in the spirit of a gospel methodology entails more than inviting heavenly participation. When we teach morally, we teach in ways that align with gospel principles and are informed by moral virtue (or Christlike attributes). Thus, in a gospel methodology, our methods of teaching are modified, in an adverbial sense, by Christlike character. This might be part of what our mission statement means when it says that BYU “must provide an environment enlightened by living prophets and sustained by those moral virtues which characterize the life and teachings of the Son of God.”

In an address at the April 2022 President’s Leadership Summit, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland suggested that the fourth section of the Doctrine and Covenants provides a powerful list of Christlike attributes that might inform our gospel methodology: “And faith, hope, charity and love, with an eye single to the glory of God, qualify him for the work. Remember faith, virtue, knowledge, temperance, patience, brotherly kindness, godliness, charity, humility, diligence” (D&C 4:5–6).

One way to follow Elder Holland’s counsel is to remember that faith, hope, charity, and love with an eye single to the glory of God are prerequisite for teaching at BYU. With these embodied attributes, faculty should then teach faithfully, virtuously, knowledgeably, temperately, patiently, kindly, charitably, humbly, and diligently. In this respect, we might strive to patiently explain key concepts of our disciplines in relation to key doctrine of the restored gospel, kindly respond to student questions with grace for the novice learner, humbly acknowledge gaps in our own subject-matter understanding, temperately react to misinformed or misguided student comments (especially those that differ from our own ideological commitments), diligently prepare lesson plans to meet the needs of individual learners (instead of teaching to some hypothetical “average” student), and so forth.

An additional delineation of Christlike attributes germane to teaching morally is found in Doctrine and Covenants 121:41–43: “No power or influence can or ought to be maintained by virtue of the priesthood, only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned; by kindness, and pure knowledge, which shall greatly enlarge the soul without hypocrisy, and without guile—reproving betimes with sharpness, when moved upon by the Holy Ghost; and then showing forth afterwards an increase of love toward him whom thou hast reproved, lest he esteem thee to be his enemy.”

In an effort to incorporate these Christlike attributes into our teaching, we might seek to gently persuade students to recognize the reasonableness of opposing viewpoints; meekly accept the limits of discipline-specific rationality and reason; guilelessly design assessments that accurately measure student learning—without cunning and clever artifice employed to trick students under the guise of rigor; genuinely and lovingly balance justice and mercy in grading assignments, papers, and exams; compassionately correct student missteps and mistakes; inspirationally provide feedback on written student work that is timely and exact; magnanimously show an increase of love after any possible perception of negative reproof; and honestly (without hypocrisy) set expectations for ourselves that match our expectations for our students.

Importantly, these expressions of Christlike character are not techniques and methods in the strict sense; rather, they represent the manner in which certain techniques and methods are enacted. Likewise, these expressions are suited to individual faculty, such that these attributes might modify our individual teaching methods in unique ways. In short, and in essence, we as faculty teach who we are. Some of us might be more naturally inclined to exhibit certain Christlike attributes in certain ways than others. Similarly, we all have different spiritual gifts that we will naturally bring to bear on our teaching. Our collective diversity of gifts immeasurably enhances the cumulative power of our teaching on this campus.

In all of these ways, we as faculty can employ morally good methods that are rooted in gospel principles. We can teach in ways that are morally good in a gospel sense.

3. Acting and Not Being Acted Upon

Quality teaching through gospel methodology—effectively teaching morally good subject matter with morally good methods—places paramount importance on the Christlike attributes and capacities of faculty and how those attributes inform our teaching practice. However, gospel methodology also requires an approach that places demands on the attributes and capacities of students—particularly on their capacity to choose (exercise moral agency) and their capacity to receive personal revelation (exercise faith). Gospel methodology, in other words, requires that we teach in ways that empower students to exercise their moral agency, to act and not simply be acted upon. “And because that they are redeemed from the fall they have become free forever, knowing good from evil; to act for themselves and not to be acted upon” (2 Ne. 2:26).

When we employ gospel methodology in our teaching, we provide opportunities for learners to act—and not simply be acted upon by us or by the course content. Put another way, we teach in ways that place maximum demand on the agency and intelligence of the learner. When we teach in ways that give students an opportunity to act for themselves, we provide a rich and engaging curriculum with multiple pathways for agentic learning and development. Most often, these pathways are grounded in our students’ questions—including their questions of the heart—and we provide scaffolding to support student growth. In this way, we can serve as mentors, guiding student learning in a subject-matter path that closely follows disciplinary norms and expectations. Within those content area standards, we hold students accountable. We also place maximum demand on our students’ intelligence and agency by identifying the level at which they can learn with (and only with) our assistance. In all of this, we must never seek disciples of our own but must strive instead to strengthen our students as disciples of Christ.

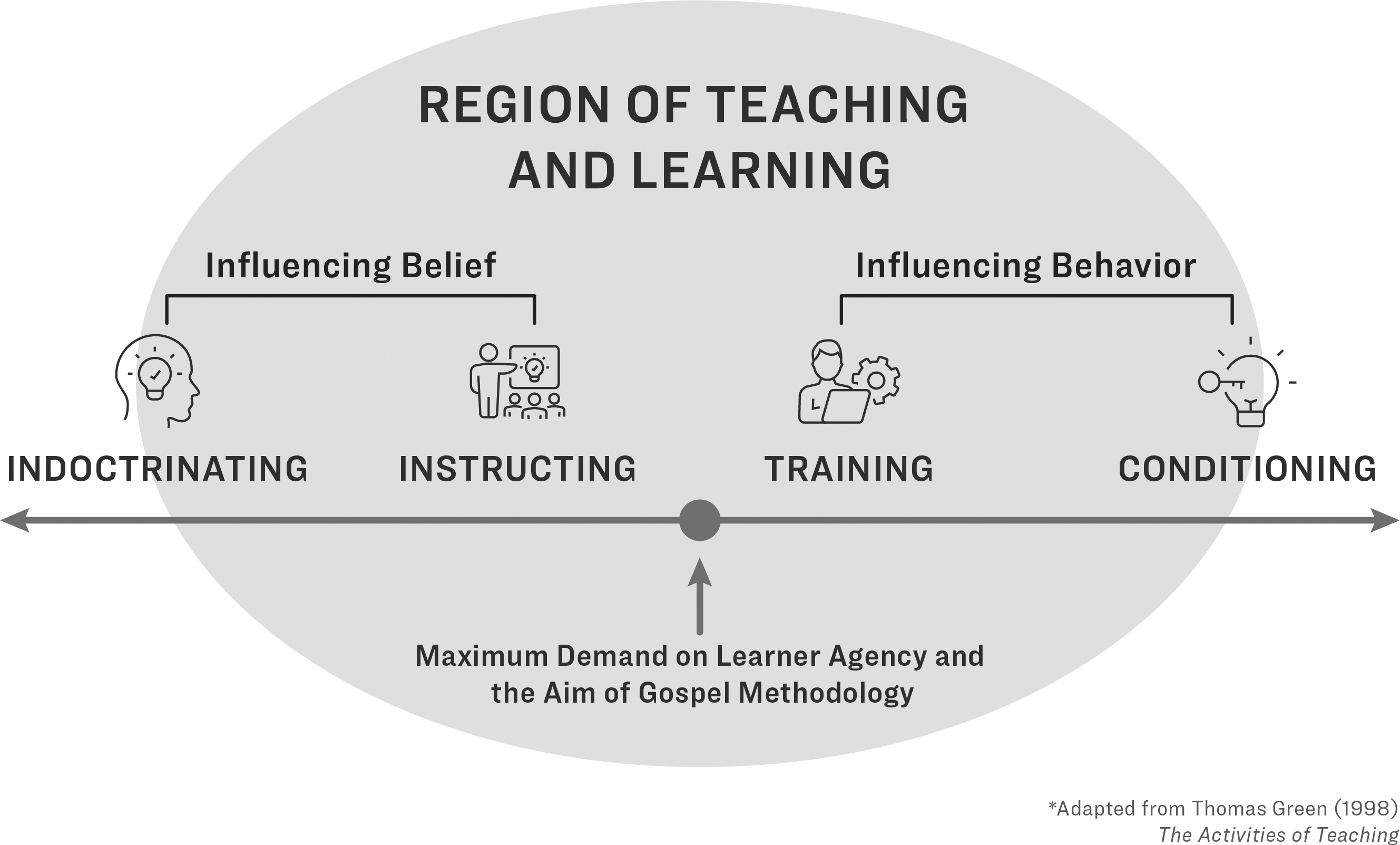

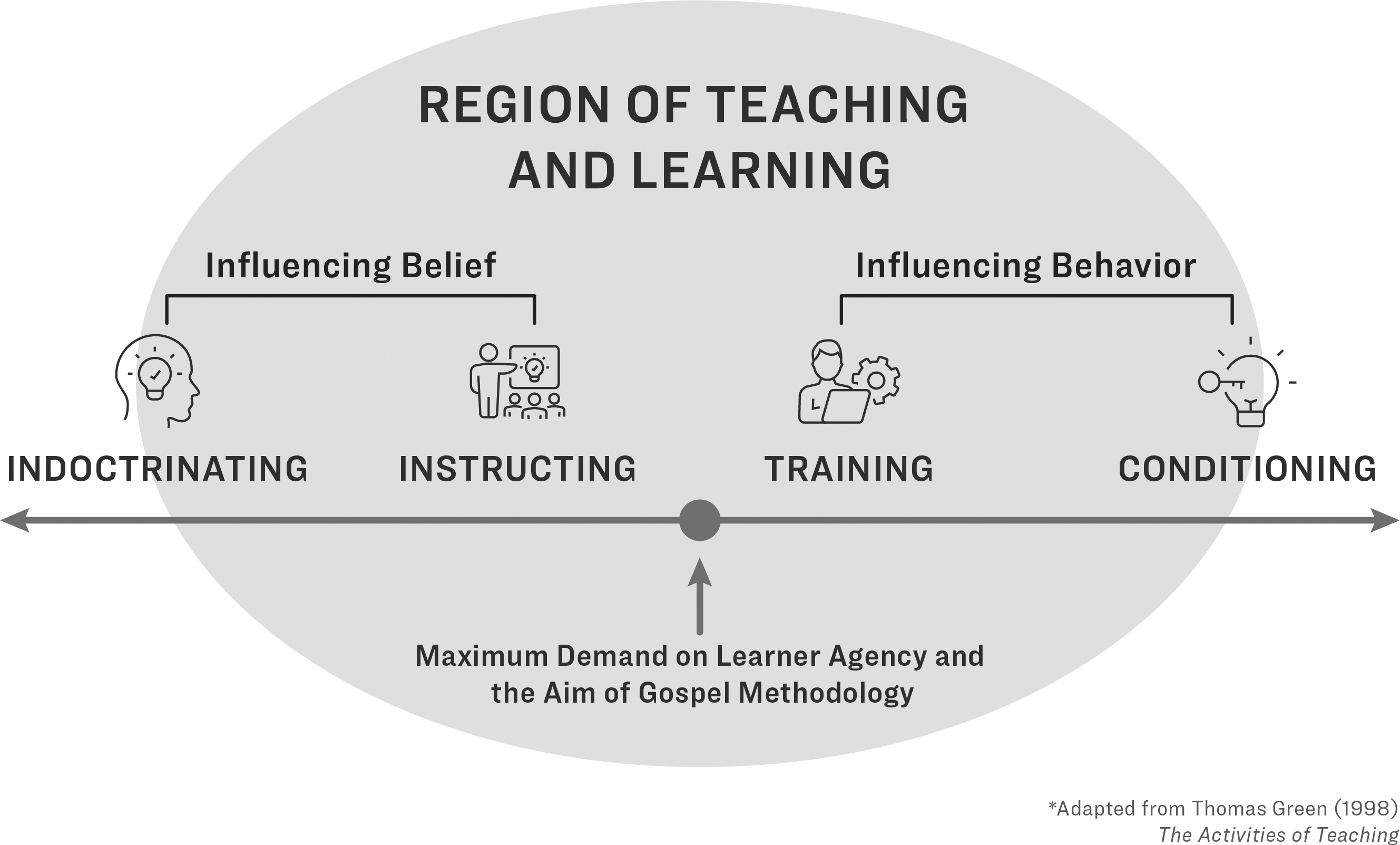

To illustrate what it means to methodologically maximize the intelligence and agency of the learner, consider the continuum of teaching in figure 1. This continuum displays how we as faculty might influence either the behavior or beliefs of our students through teaching methods that place less and less demand on their agency as the methods move further away from the midpoint. For example, instead of placing maximum demand on the agency and intelligence of the learner, we might (less desirably) instruct the learner in a certain set of beliefs or even attempt to indoctrinate the learner by encouraging uncritical acceptance of a set of true beliefs. Instruction is certainly a form of teaching that places some requirement on the agency and intelligence of the learner (particularly instruction that involves discussion of reasons for belief). Indoctrination, however, places little to no demand on the agency and intelligence of the learner. When indoctrination aims to instill beliefs that ultimately contribute to reasoned, intelligent, or inspired understanding, it might be considered a form of teaching. However, if inculcating certain beliefs is the end goal—without any future attention to the reasons or justification for those beliefs—then indoctrination is not teaching.

Figure 1

Figure 1. Continuum of Teaching in a Gospel Methodology. Adapted from Thomas Green,

The Activities of Teaching (New York: Educator’s International Press, 1998).

Similarly, to influence the behavior of the learner, we can also engage in teaching practices that do not place maximum demand on the learner’s agency and intelligence. As we move away from this maximum demand, we risk engaging in techniques and strategies that run counter to gospel methodology. For example, to influence the behavior of the learner we might appropriately provide training in a certain skill or technique, but we might also mistakenly attempt to condition learners to mindlessly change their conduct in response to certain rewards or consequences. Training is certainly a form of teaching that places some requirement on the agency and intelligence of the learner, particularly when that behavior is an “expression of intelligence.” Similarly, when conditioning occurs as a way of training certain behaviors that will lead to intelligent expression, then it might be considered a form of teaching. However, if conditioning certain behaviors is the goal—simply an automatic response to stimuli—then conditioning is not teaching.

Within this region of teaching and learning, it is possible for learners to act, exercise their capacity to choose, and engage their intellect. But once we, as faculty, cross the line of this region, even as we begin leaving the midpoint where maximum demand is placed on the learner’s agency and intelligence, we are simply acting upon the learner. We are manipulating a change in behavior or seducing a change in belief (miseducation). Whereas the region of teaching and learning includes most forms of training and instructing (as well as some kinds of conditioning and indoctrinating), the region of gospel methodology is constrained much more closely to the midpoint.

This important principle of gospel methodology (and the line that cannot be crossed) is well described in Doctrine and Covenants 121, which warns against exercising “control or dominion or compulsion upon the souls of the children of men, in any degree of unrighteousness” (v. 37). The call to resist unrighteous dominion and compulsion does not preclude us from exerting authoritative influence, but any such influence must be moderated by Christlike attributes. Our influence, like our teaching methods, must be animated “by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned; by kindness and pure knowledge, which shall greatly enlarge the soul without hypocrisy, and without guile” (vv. 41–42).

There is no room within gospel methodology for unrighteous dominion—including forms of indoctrination and conditioning. Our influence as faculty should be exerted only in gentle, loving ways devoid of cunning or coercion. Gospel methodology thus requires more than conditioning or indoctrinating, and even more than training and instructing (although these methods can certainly be applied appropriately and morally). Avoiding hypocrisy and guile is a minimum threshold; placing maximum demand on the intelligence and agency of the learner is the aspiration. This component of gospel methodology leads to learning that lasts because “without compulsory means it shall flow unto [the learner] forever and ever” (D&C 121:46).

4. By Study and By Faith

Like the principle of moral agency, the capacity of the learner to receive personal revelation is another component of gospel methodology that places demands on the attributes and capacities of students (as well as of faculty). As teachers, we should seek revelation for ourselves and strive to foster revelation among learners. In section 88 of the Doctrine and Covenants, described by President Dallin H. Oaks as “the basic constitution of Church education,” it is prophetically clear that we are to learn by both study and faith: “And as all have not faith, seek ye diligently and teach one another words of wisdom; yea, seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom; seek learning, even by study and also by faith” (v. 118, emphasis added).

The capacity to receive personal revelation is rooted squarely in the first principle of the gospel—faith—and represents the most dramatic and unique departure from what might be considered an appropriate methodology at other universities committed to principles and practices of quality teaching. That is, faculty at any university might reasonably be expected to effectively teach morally good content in morally good ways while placing maximum demand on the agency of the learner. However, there would certainly be no expectation in that generic methodology for any attention to the exercise of faith and the pursuit of personal revelation. At BYU, “learning that leads to inspiration or revelation” was beautifully described by former president Kevin J Worthen as “inspiring learning.”

This inspiring component of gospel methodology resides in epistemologies of practice that the secular academy has long since abandoned in favor of an exclusive focus on more scientifically trusted empirical and rational ways of knowing. There is no serious methodological debate within the broader academy that questions the primary or even sole reliance on observation, sensory perception, logic, and reason over inspiration and revelation (particularly as a product of faithful exercise).

Within gospel methodology, by contrast, we provide opportunities for our students to learn both by study and by faith. We design assignments and class activities that encourage or perhaps even require the exercise of faith and lead to inspiring learning. These assignments and activities call on students to place their trust in God, who “giveth . . . liberally” to those who ask (James 1:5). They also encourage students to trust not the “arm of flesh” (2 Ne. 4:34) and to trust in the Lord instead—leaning not unto their own understanding (Prov. 3:5).

Notably, in a gospel methodology, learning by study and by faith is not an either/or proposition. We learn by study and by faith or, put another way, by study-and-faith. That is, our exercise of faith complements empirical and rational ways of knowing in a manner that opens the door to revelation and inspiration: “Observation, reason, and faith facilitate revelation and enable the Holy Ghost to be a reliable, trustworthy, and beloved companion.” It is in this synergistic approach to learning that “belief enhances inquiry, study amplifies faith, and revelation leads to deeper understanding.”

Such assignments, activities, and discussion require students to seek revelation—to be inspired—not simply to absorb and then recite the presented facts, figures, and ideas of faculty or to simply “download” the information from a text. When students learn by faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, they access the enabling power of his Atonement to increase in understanding. In this way, the inspired ideas (not rote facts) come from the heavens through personal revelation, and they belong to the learner. The learning experience increases the student’s capacity to receive revelation, instead of the student’s capacity to release regurgitation. And instead of a perfunctory performance, prayer becomes the most important instrument for accessing answers and fueling creative capacity.

Gospel methodology thus creates conditions that require us not only to imbue our methods with gospel principles but also to provide opportunities for students to apply gospel principles to their learning. Through carefully constructed learning experiences, students exercise their agency and their faith. They are given opportunities to act (to be anxiously engaged and not simply acted upon) and thereby to increase their capacity to choose. And, similarly, they are required to learn not only by study but also by faith (to seek inspiration for answers to their subject matter questions) and thereby to increase their capacity to receive personal revelation.

5. By the Spirit and with the Spirit

These components of gospel methodology represent a loose framework for thinking about how we, as faculty, apply gospel principles and concepts to our teaching. There are surely many other ways to conceptualize and operationalize an approach to teaching that is rooted in the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. However, it would be difficult to suggest that any conceptualization would be complete without underscoring the essential role of the Holy Ghost in gospel methodology. Gospel methodology imposes the same exacting standard as all divinely approved teaching: “Verily I say unto you, he that is ordained of me and sent forth to preach the word of truth by the Comforter, in the Spirit of truth, doth he preach it by the Spirit of truth or some other way? And if it be by some other way it is not of God” (D&C 50:17–18).

Any other way is not of God; any other way is not gospel methodology. This perspective is particularly important at BYU, given the oft-quoted prophetic admonition from President Brigham Young to Dr. Karl Maeser (the then–newly called principal of Brigham Young Academy): “You ought not to teach even the alphabet or the multiplication tables without the Spirit of God.”

Consistent with this charge, which John Tanner has called “BYU’s prime directive,” we as faculty must recognize the role of the Holy Spirit in every aspect of teaching and learning at BYU. We must teach both by the Spirit and with the Spirit. That is, the Spirit must both inform what we teach and carry our teaching into student minds and hearts.

When we teach by the Spirit, we teach to some extent like the prophet Nephi of old—not knowing beforehand where we are going or what we should do: “And I was led by the Spirit, not knowing beforehand the things which I should do” (1 Ne. 4:6, emphasis added).

This of course does not mean that we don’t prepare lessons or define learning outcomes beforehand. As President Boyd K. Packer often counseled, “We first adopt, then we adapt.” But we can also create structured opportunities to teach as directed by the Spirit, to engage in meaningful discussion based on the questions of learners. In this respect, inspiration can inform method midstream.

Similarly, in those structured opportunities for student learning, we can teach with the Spirit. When we teach with the Spirit, we teach in a way that invites the Holy Ghost to communicate the content to the learner’s heart and mind.

This component of gospel methodology is possible only when we as faculty place maximal demand on our students’ agency, intelligence, and faith. Likewise, it requires testimony of gospel truth or belief in disciplinary content (bathed in the light of the restored gospel) to call upon the Spirit to accompany the message. In these sacred moments, regardless of the subject matter (the gospel itself or disciplinary content), the Spirit does the teaching. Moreover, an approach to teaching that relies on the Spirit of God—and that honors learners’ agency and faith—also highlights our aspiration that all will have an “equal privilege” to speak and participate so that “all may be edified of all” (D&C 88:122). In a large university setting, this aspect of teaching by and with the Spirit possibly poses the biggest challenge—but also presents the greatest opportunity—for gospel methodology.

Conclusion

Gospel methodology requires a consecrated faculty. This requires more than faculty who are willing to teach the gospel. It requires faculty who engage in quality teaching practices and teach in consecrated ways—who teach morally good content with morally good methods. These methods draw on both our character as faculty—the Christlike attributes we cultivate—and on our employment of a pedagogy of the Spirit that places demand on the agency, intelligence, and faith of our students. Such a methodology results in inspiring learning and gives both students and faculty access to the moral rewards that are internal to the practice of teaching. These rewards include a sense of common cause in the most important work on the earth today and point Brigham Young University to the most magnificent realization of its sacred mission: to assist others in their quest for perfection and eternal life.

Appendix

The following notes provide additional commentary on substantive, important points that do not necessarily stand alone as principles of a gospel methodology. Each point is connected to a specific principle and provides additional commentary, reflection, or elaboration.

1. Heuristic Framework. The principles of a gospel methodology presented herein should not be interpreted as a set of procedures that, if followed, will result in certain learning outcomes (related to a given subject matter or the gospel itself). Just as it would be a mistake to conclude that a certain technique for teaching a particular concept or skill will automatically lead to comprehension or expertise, there is no gospel methodology that guarantees perfection and eternal life. This lack of guarantee is, in part, due to the agency of the learner. It is also related to the “ontological dependence” of teaching and learning—the idea that the concept of teaching is conditioned on learning occurring at some point, but not always (similar to the way that one might race and not win or fish and not catch fish). Put simply, these principles of gospel methodology should be interpreted as a loose heuristic framework for examining, and possibly improving, teaching practices in a direction that is aligned with the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. Any purposeful and positive result would be a product of moving in that direction but would not be caused by the scripted implementation of certain techniques or strategies.

2. Importance of Prayer. If asked, faculty and students would likely suggest that the most obvious and prevalent component of gospel methodology is a prayer to begin class (and, possibly, an accompanying spiritual thought). Proponents of a rich conception of gospel methodology would correspondingly point out that a prayer to begin class is only one part of a much larger whole. Unfortunately, such an argument runs the risk of diminishing the importance of prayer in classrooms at BYU, if we interpret this exchange as a criticism of prayer itself. When viewed as censure or reproval, it is possible to mistakenly conclude that prayer is an insignificant piece of a gospel methodology because prayer is a simple, basic, ordinary way to begin class—quite disconnected and separate from the content of the lesson plan and disciplinary subject matter.

Of course, if the prayer to begin class is a perfunctory one, then the claim for insignificance is accurate. However, even in the most expansive view of gospel methodology, it is difficult to identify a more important component than heartfelt, fervent prayer. The restoration of the gospel itself began with Joseph’s prayer, and there are countless invitations in the scriptures, such as to “pray always, and not faint; that ye must not perform any thing unto the Lord save in the first place ye shall pray unto the Father in the name of Christ” (2 Ne. 32:9, emphasis added). In this way, prayer finds itself in “first place” in a gospel methodology and is the key to a consecrated performance.

When we as faculty, along with our students, “ask in faith, nothing wavering” (James 1:6), we stand as witnesses of one of the most fundamental doctrines of the restoration—that the heavens are open. The strength and subsequent application of this witness depend not only on the faith of the believers (faculty and students) but also on the appropriateness of the context—namely, the lack of wisdom. The heavens stand ready to give liberally to those of us who lack wisdom and ask in faith, but it then follows that we need to organize our class instruction and activities in ways that require such supplication to the heavens. In our preparations for classroom instruction and activity, we might do well to ask ourselves, “Am I teaching anything in any way today that would benefit from heavenly assistance—to either my students or myself?”

3. Rigor and Unrighteous Dominion. When academic rigor is interpreted as setting high expectations for students that challenge students’ intellect and capacities at a level just beyond their reach without assistance from faculty, then we help students realize the intellectual purposes of higher education (and the Aims of a BYU Education). In this spirit of rigor, students should embrace challenge and struggle as an important part of their academic learning, growth, and development. However, at times we substitute a different understanding of rigor for this elevated, even sacred sense of challenge, struggle, adversity, and trial. This divergent application of rigor to academic learning is more akin to rigidity, inflexibility, cruelty, and authoritarianism. In this sense, rigor is connected to methods of instruction (mechanical, preprogrammed lectures), assessments (cunning/deceptive exams), or assignments (excessive reading or busy work) that overburden students. And the content is overly complex.

Notably, in this approach to teaching and learning, it is not possible for us, as faculty, to intervene in any meaningful way to improve the experience. The challenge to the students’ intellect and capacities is too far beyond their own reach—and no faculty assistance will help those students overcome the substantial gap. That is, there is nothing in this approach that lends itself to remedial teaching—it goes without saying that there is no helpful remedy connected to additional preprogrammed lectures, more deceptive exams, or extra excessive reading and busywork.

In this way, the pursuit of academic rigor becomes a form of unrighteous dominion. As faculty, we place the desire for difficulty—particularly hardship that places no demand on us to intervene—above the well-being and ultimate learning of students. The move toward unrighteous dominion, in such a case, is the prioritization of an unreachable standard with rigid, inflexible, authoritarian expectation: “It emphasizes tasks and agendas at the expense of human relationships and the welfare of souls.” In this sense, “we should never reprove beyond the capacity of our healing balm to reach out to the person reproved.” Placing any expectation on students without placing concomitant responsibility on ourselves to successfully support those students creates the potential for unrighteous dominion. The expectations for students in any class must be accompanied by adequate pedagogically appropriate scaffolding provided by faculty.

4. Grading. It would likely prove an impossible task to have all faculty, across all disciplines, come to an agreement on what a gospel methodology entails for grading students. But the improbability of the quest should not prevent us from embracing a paramount gospel principle for grading—namely, that “God is no respecter of persons” (Acts 10:34). Such a tenet does not mean that students should not be held accountable for their learning, nor does it mean that some students will not learn more than others, nor even does it preclude the possible ranking and sorting of student performance. However, this gospel truth does suggest that the results of grading should not be predetermined by students’ backgrounds. In other words, when grading reinforces achievement gaps between groups of students, it is possible that some element of the course pedagogy or grading procedure has departed from gospel methodology. Some preexisting disparities might persist stubbornly despite a teacher’s best efforts to employ gospel methodology, and it remains a reality that our students come to us with varying levels of general academic and subject-matter preparation. But we should never be complacent on this front. These types of achievement gaps exist at every level of education, including higher education, but it is the office of a teacher and of a university to work to reduce them. This is especially true for teachers at BYU with a shared commitment to the restored gospel of Jesus Christ and to teaching with gospel methodology.

5. Spiritual Gifts. It would be a mistake to assume that all faculty ought to exhibit the same Christlike attributes in exactly the same way. As with the conferral of spiritual gifts, it is likely that “to some it is given” to teach morally in one way and to some in another. We all have different gifts as teachers, and those gifts are conditioned differently by our individual development of appropriate Christlike attributes that modify our practice. In this respect, the congruity with which some faculty naturally connect their Christlike character to their practice is likely a product of their seeking “earnestly the best gifts” (D&C 46:8). Moreover, it is a strong tenet of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ that all of God’s children can develop such spiritual gifts and Christlike character—it is a gospel of repentance and change (Alma 5:12–13), or what President Nelson has called a “gospel of healing and progression.” Thus, we should cultivate those Christlike aspects of our character that are most readily applicable to our practice and also earnestly seek the best gifts, enabling the Savior to “make weak things become strong” (Ether 12:27).

6. The Region of Teaching and Gospel Methodology. On the continuum of teaching (see fig. 1), there are approaches to teaching and gospel methodology that certainly include meaningful instruction and training. For example, a student might be trained in a certain procedure for a lab experiment or be instructed that racism should be rooted out. Such training and instruction might, for well-intended reasons, initially avoid explaining the underlying science or articulating the underlying doctrine. But if we are to implement gospel methodology more fully, we must at some point move toward more agentic, intelligent learning. If our goal is to simply encourage conditioned response to stimuli or uncritical acceptance of belief, then our methods fall outside the region of teaching and gospel methodology. The same is true a fortiori if we try to condition a response or belief based on premises or foundations that are incompatible with the truths of the restored gospel. In all of this, it is important to remember that because gospel methodology is always moving toward placing maximum demand on the intelligence and agency of the learner, merely instructing, indoctrinating, training, or conditioning will never be sufficient.

7. Moral Rewards of Teaching. The payoff for the learner in a gospel methodology is self-evident and reflected in the learning outcomes of the course. In broad terms, students experience meaningful learning that lasts—perhaps best described as “understanding.” But there are also rewards, including moral rewards, for the faculty. Moral rewards might include increased self-efficacy and fulfillment, an enhanced sense of common cause, a heightened awareness of noble and sacred purpose, genuine contentment with practice, greater satisfaction with authentic student participation, and more meaningful connection with students. Access to these moral rewards is contingent on faculty teaching morally (employing the Christlike attributes of a gospel methodology) because the goods internal to a practice are available to faculty only when they exercise virtue.

Put another way, moral rewards are not achieved simply by engaging in certain types of practices or pedagogy. When learning outcomes are not the direct result of teaching methods that are modified by moral virtue (teaching morally), then the moral rewards are not accessible to us as faculty. Simply going through the motions brings no sense of fulfillment, no enhancement of common cause, no genuine satisfaction, no strengthened relationship. In this way, the goods associated with any practice might be external, internal, or both. But the achievement of goods internal to a practice are accessible only through the exercise of moral virtue (Christlike character). If we are to feel a sense of fulfillment in helping a struggling student, for example, then we will need to exhibit patience, long-suffering, and diligence in our teaching. In a purely gospel-methodology sense, this type of moral reward might be captured best in the Book of Mormon’s description of how Alma and the sons of Mosiah felt a sense of common cause and an awareness of sacred shared purpose when they reunited as “brethren in the Lord” after their patient, long-suffering, diligent, prayerful work as missionaries (Alma 17:2–3).

Notably, these moral rewards—internal to the practice of teaching—are sometimes elusive for us because the focus of evaluation for professors is so squarely rooted in external rewards. The goods external to the practice of teaching include advancement in rank and status, high student evaluations, honors and awards, praise of colleagues, and so forth. Of course, a gospel methodology points away from any gratification of pride, vain ambition, and honors of men (D&C 121), but such honors are certainly valued and even expected in academe. Perhaps the greatest loss in this misplaced focus is that it precludes access to the moral rewards of teaching. And this potential loss highlights the perverse nature of the incentives (often stipulated or recognized in policy) that are supposed to motivate us as faculty. Moral rewards provide a particularly sweet fruit for faculty who employ gospel methodology.

Figure 1. Continuum of Teaching in a Gospel Methodology. Adapted from Thomas Green, The Activities of Teaching (New York: Educator’s International Press, 1998).

Figure 1. Continuum of Teaching in a Gospel Methodology. Adapted from Thomas Green, The Activities of Teaching (New York: Educator’s International Press, 1998).