Notes

1. See, for instance, “History, 1838–1856, Volume B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838],” 596, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 13, 2022, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-b-1-1-september-1834-2-november-1838/50; “John Whitmer, History, 1831–circa 1847,” [76], in Histories, Volume 2: Assigned Histories, 1831–1847, ed. Karen Lynn Davidson, Richard L. Jensen, and David J. Whittaker, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 86; and Warren Parrish, letter to the editor of the Painesville Republican, February 5, 1838, in “Mormonism,” Painesville Republican 2, nos. 14–15 (February 15, 1838): [3].

2. “Journal, 1835–1836,” November 19, 1835, 46, in Journals, Volume 1: 1832–1839, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), 107.

3. “Editorial, circa 1 March 1842, Draft,” 1, in Documents, Volume 9: December 1841–April 1842, ed. Alex D. Smith, Christian K. Heimburger, and Christopher James Blythe, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2019), 207. See also Wilford Woodruff, “Letter to Parley P. Pratt, 12 June 1842,” [3], Wilford Woodruff Papers, https://wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/documents/1981baad-5423-44bb-905b-cd4339c8f85d/page/aa122c61-597f-4e47-ac2b-9278833b3ca3: “The Saints abroad manifest much interest in the Book of Abraham in the T[imes] & Seasons it will be continued as fast as Joseph gets time to translate.”

4. “The Book of Abraham,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 9 (March 1, 1842): 704.

5. “Persecution of the Prophets,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 21 (September 1, 1842): 902.

6. While learning Hebrew, the Prophet spoke of “studying,” “reading,” “learning,” and “translating” biblical Hebrew in journal entries dated January 26, 29; February 1, 3, 5, 9, 11–13, 15, 21–23, 26–28; and March 10, 16, 24–25, 29, 1836. See “Journal, 1835–1836,” 142–185, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 13, 2022, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/journal-1835-1836/143. For a discussion, see Matthew J. Grey, “‘The Word of the Lord in the Original’: Joseph Smith’s Study of Hebrew in Kirtland,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 249–302.

7. See the overview and discussion in Kerry Muhlestein, “Book of Abraham, Translation Of,” in The Pearl of Great Price Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 63–69; Kerry Muhlestein, “Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Introduction to the Historiography of Their Acquisitions, Translations, and Interpretations,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 22 (2016): 32–39; Hugh Nibley, “Translated Correctly?,” in The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 16 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 2005), 51–65; and Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2018), xxii–xxvi.

8. “Church History,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 9 (March 1, 1842): 707.

9. David E. Sloan, “The Anthon Transcripts and the Translation of the Book of Mormon: Studying It Out in the Mind of Joseph Smith,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 57–81.

10. See Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, “Firsthand Witness Accounts of the Translation Process,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, ed. Dennis L. Largey and others (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 61–79; and Michael Hubbard MacKay and Nicholas J. Frederick, Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2016).

11. John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 20.

12. For an overview, see Michael Hubbard MacKay, “‘Git Them Translated’: Translating the Characters on the Gold Plates,” in Blumell, Grey, and Hedges, Approaching Antiquity, 83–116; and Brant A. Gardner, “Translating the Book of Mormon,” in A Reason for Faith: Navigating LDS Doctrine and History, ed. Laura Harris Hales (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2016), 21–32.

13. Ulisses Soares, “The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon,” Ensign 50, no. 5 (May 2020): 33.

14. “Account of John, April 1829–C [D&C 7],” in Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831, ed. Michael Hubbard MacKay and others, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 47–48. For the historical context of this section, see Jeffrey G. Cannon, “Oliver Cowdery’s Gift: D&C 6, 7, 8, 9, 13,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 15–19; and David W. Grua and William V. Smith, “The Tarrying of the Beloved Disciple: The Textual Formation of the Account of John,” in Producing Ancient Scripture: Joseph Smith’s Translation Projects in the Development of Mormon Christianity, ed. Michael Hubbard MacKay, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Brian M. Hauglid (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2020), 231–61.

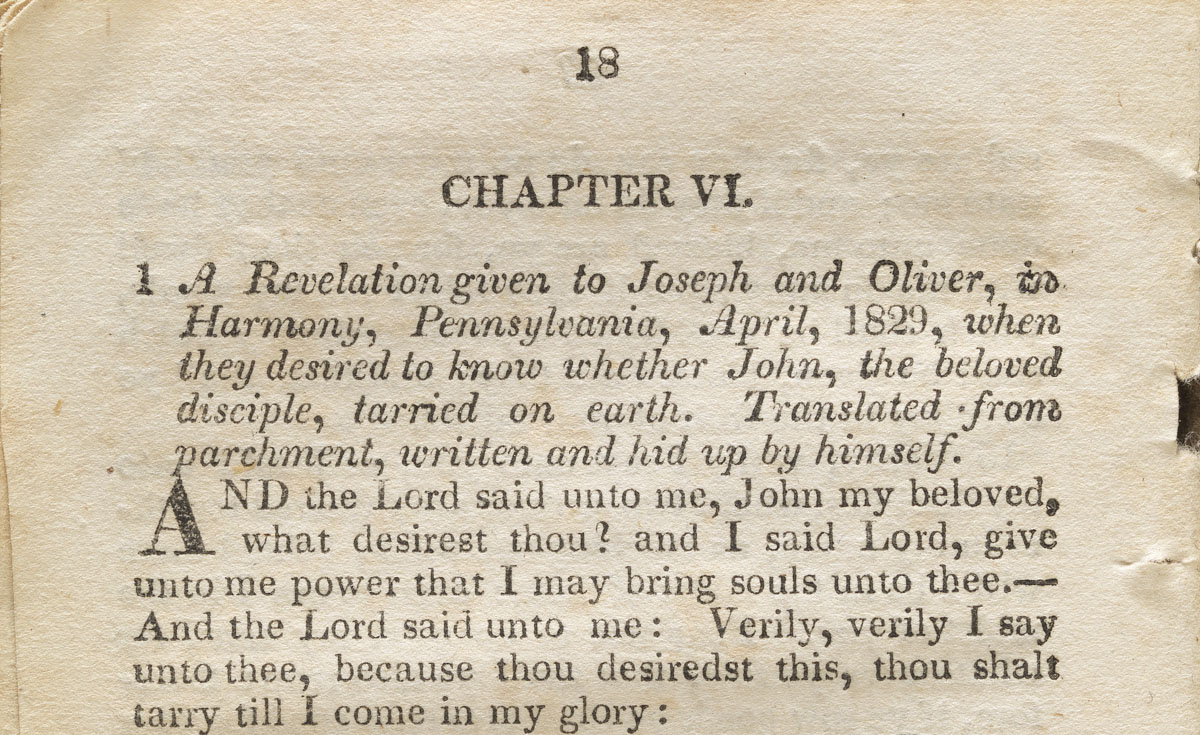

15. “Chapter VI.,” in A Book of Commandments, for the Government of the Church of Christ, Organized according to Law, on the 6th of April, 1830 (Independence, Mo.: W. W. Phelps, 1833), 18. In the Manuscript Revelation Book, this section is called a “commandment” and a “revelation” but not explicitly a “translation.” “Revelation Book 1,” in Revelations and Translations, Volume 1: Manuscript Revelation Books, ed. Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), 15.

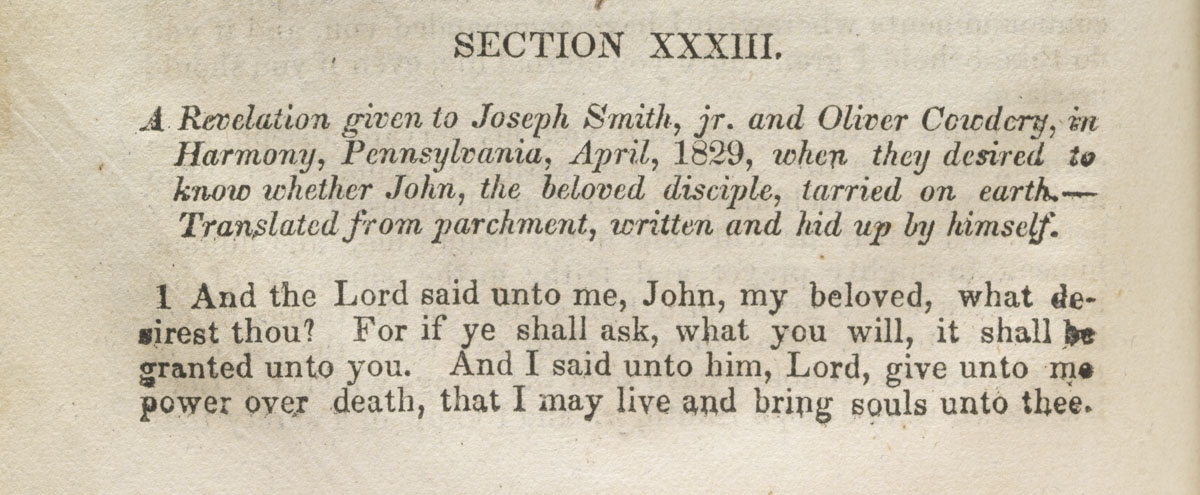

16. “Section XXXIII,” in Doctrine and Covenants of the Church of the Latter Day Saints: Carefully Selected from the Revelations of God (Kirtland, Ohio: F. G. Williams and Company, 1835), 160; “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 18 (July 15, 1842): 853. See the observation in Robert J. Woodford, “The Historical Development of the Doctrine and Covenants,” 3 vols. (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1974), 1:176.

17. “History, 1838–1856, Volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834],” 15, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 13, 2022, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834/21.

18. Gee, Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 21; compare MacKay and others, Documents, Volume 1, 48 n. 129.

19. Grua and Smith, “Tarrying of the Beloved Disciple,” 254–60.

20. “Letter to Church Leaders in Jackson County, Missouri, 25 June 1833,” [1], and “Letter to Church Leaders in Jackson County, Missouri, 2 July 1833,” 52, in Documents, Volume 3: February 1833–March 1834, ed. Gerrit J. Dirkmaat and others, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2014), 154, 167.

21. See Robert J. Matthews, “A Plainer Translation”: Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible—a History and Commentary (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1975); Kent P. Jackson, “Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible,” in Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 51–76; Kent P. Jackson, “The King James Bible and the Joseph Smith Translation,” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 197–214; Royal Skousen, “The Earliest Textual Sources for Joseph Smith’s ‘New Translation’ of the King James Bible,” FARMS Review 17, no. 2 (2005): 451–70; Royal Skousen, The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon. Part Five: The King James Quotations in the Book of Mormon (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2019), 132–40; Jared W. Ludlow, “The Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible: Ancient Material Restored or Inspired Commentary? Canonical or Optional? Finished or Unfinished?,” BYU Studies Quarterly 60, no. 3 (2021): 147–57; and Kent P. Jackson, Understanding Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2022).

22. Early chapters of the original manuscript of JST Genesis 1–24 are prefaced by scribal notes such as: “A Revelation given to Joseph the Revelator June 1830” (preface to Moses 1), “A Revelation given to the Elders of the Church of Christ On the first Book of Moses” (preface to Moses 2/Genesis 1), “A Revelation concerning Adam after he had been driven out of the garden of Eden” (preface to Moses 5/Genesis 4). See “Old Testament Revision 1,” [1], 3, 8, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 13, 2022, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/old-testament-revision-1/3. Many years after the project was finished, Orson Pratt recalled witnessing Joseph Smith dictate his revisions to the Bible while under the inspiration of God. “He was inspired of God to translate the Scriptures,” wrote Pratt in 1856, speaking of the JST. Orson Pratt, “Spiritual Gifts” (n.p., 1856), 71. A few years later, Pratt said in a sermon how he “saw [Joseph Smith’s] countenance lighted up as the inspiration of the Holy Ghost rested upon him, dictating the great and most precious revelations now printed for our guide.” Pratt specifically remembered seeing Joseph “translating, by inspiration, the Old and New Testaments, and the inspired book of Abraham from Egyptian papyrus.” Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1855–86), 7:176 (July 10, 1859). That Pratt mentioned the JST and the Book of Abraham together may be significant in how Joseph Smith’s contemporaries understood and contextualized these two scriptural productions.

23. “New Testament Revision 1,” 1, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed December 13, 2022, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/new-testament-revision-1/5.

24. See Thomas A. Wayment, “Intertextuality and the Purpose of Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible,” in Foundational Texts of Mormonism: Examining Major Early Sources, ed. Mark Ashurst-McGee, Robin Scott Jensen, and Sharalyn D. Howcroft (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 74–100; Thomas A. Wayment, “Joseph Smith, Adam Clarke, and the Making of a Bible Revision,” Journal of Mormon History 46, no. 3 (July 2020): 1–22; and Thomas A. Wayment and Haley Wilson-Lemmon, “A Recovered Resource: The Use of Adam Clarke’s Bible Commentary in Joseph Smith’s Bible Translation,” in MacKay, Ashurst-McGee, and Hauglid, Producing Ancient Scripture, 262–84. Kent P. Jackson, “Some Notes on Joseph Smith and Adam Clarke,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 40 (2020): 15–60, has critiqued the claim that Joseph Smith relied on Adam Clarke’s commentary. The question of how dependent Joseph Smith may have been on Adam Clarke or other sources remains an open one.

25. Jackson, Understanding Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible, 31–37, discusses the types of changes that Joseph Smith appears to have made to the Bible, including restoring original text, restoring things said or done but never recorded in the Bible, modernizing the language of the Bible, harmonizing biblical passages with themselves or with modern revelation, and “common sense” revising to correct errors. These are in addition to a number of other possibilities, which include instances of the Prophet, by revelation, giving more precise renderings of the original languages. See also Matthews, “Plainer Translation,” 253; and Scott H. Faulring, Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds., Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004), 8–11.

26. Nicholas J. Frederick, “Translation, Revelation, and the Hermeneutics of Theological Innovation: Joseph Smith and the Record of John,” in MacKay, Ashurst-McGee, and Hauglid, Producing Ancient Scripture, 304–27.

27. Compare Robert J. Matthews, “Record of John,” in Doctrine and Covenants Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 534–35, who makes an argument that the John in this passage is John the Baptist.

28. Steven C. Harper, Making Sense of the Doctrine and Covenants: A Guided Tour through Modern Revelations (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2008), 346.

29. Harper, Making Sense of the Doctrine and Covenants, 345.

30. Matthew McBride, “‘Man Was Also in the Beginning with God’: D&C 93,” in McBride and Goldberg, Revelations in Context, 192–95.

31. McBride, “‘Man Was Also in the Beginning with God,’” 193.

32. Jensen and Hauglid, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, xxiii.

33. “John Whitmer, History, 1831–circa 1847,” 86.

34. Parrish, letter to the editor of the Painesville Republican, [3].

35. “These were days never to be forgotten—to sit under the sound of a voice dictated by the inspiration of heaven, awakened the utmost gratitude of this bosom! Day after day I continued, uninterrupted, to write from his mouth, as he translated with the Urim and Thummim, or, as the Nephites would have said, ‘interpreters,’ the history, or record, called ‘The Book of Mormon.’” Oliver Cowdery, “Dear Brother,” Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate 1, no. 1 (October 1834): 14, emphasis in original.

36. See Jay M. Todd, The Saga of the Book of Abraham (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1969), 175–77, 219–33; H. Donl Peterson, The Story of the Book of Abraham: Mummies, Manuscripts, and Mormonism (Springville, Utah: CFI, 2008), 175–76; and Stephen O. Smoot, “Did Joseph Smith Use a Seer Stone in the Translation of the Book of Abraham?,” Religious Educator 23, no. 2 (2022): 65–107.

37. “Another Humbug,” Cleveland Whig, August 5, 1835, 1. See the discussion in Smoot, “Did Joseph Smith Use a Seer Stone?,” 69–72; and MacKay and Frederick, Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones, 127–28, who suggest the newspaper’s source was actually William W. Phelps, another scribe in the Egyptian project.

38. MacKay and Frederick, Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones, 127.

39. Wilford Woodruff, “Journal (January 1, 1841–December 31, 1842),” [133–34], February 19, 1842, Wilford Woodruff Papers, https://wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/documents/a9d1a2cb-18fe-445d-a5e4-350caaf63442/page/46a50900-b577-4e5c-9fd9-6b2347845fc1; Parley P. Pratt, “Editorial Remarks,” Millennial Star 3, no. 3 (July 1842): 47; M., “Correspondence of the Friends’ Weekly Intelligencer,” Friends’ Weekly Intelligencer 3, no. 27 (October 3, 1846): 211; Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 20:65 (August 25, 1878). One of Joseph Smith’s clerks in Nauvoo, Howard Coray, also remembered seeing the Prophet “translate by the Seer’s stone” but did not specify what he saw Joseph translate. Howard Coray to Martha Jane Lewis, August 2, 1889, MS 3047, Church History Catalog, https://catalog.churchofjesuschrist.org/assets/becd2d14-e7c0-4aa8-b70d-26861581916f/0/0?lang=eng. Since Coray did not join the Church and become Joseph’s clerk until 1840, he could not have witnessed the translations of the Book of Mormon or the Bible. It would appear that, unless he meant he saw Joseph receive revelation by the seer stone, he witnessed Joseph on at least one occasion in Nauvoo translate a portion of the Egyptian papyri with the seer stone.

40. Smith, Heimburger, and Blythe, Documents, Volume 9, 204, 252–54.

41. The account in the Friends’ Weekly Intelligencer, cited above, reads thus: “When Joseph was reading the papyrus, he closed his eyes, and held a hat over his face, and that the revelation came to him; and that where the papyrus was torn, he could read the parts that were destroyed equally as well as those that were there; and that scribes sat by him writing, as he expounded.” The detail of Joseph placing his face into his hat to read the papyrus sounds much like how witnesses described the translation of the Book of Mormon, suggesting the possibility that the paper misreported or confused which text Lucy Mack Smith was describing. On the other hand, if the Cleveland Whig report is accurate and Joseph was indeed examining the papyrus with his seer stone, then perhaps Joseph’s translation methods for the Book of Mormon and the Book of Abraham were more similar than previously supposed. Furthermore, at least two other sources also indicate that Joseph was able to read and translate portions of the papyrus that were damaged. One of these sources mentions how “Smith is to translate the whole by divine inspiration, and that which is lost, like Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, can be interpreted as well as that which is preserved” (William S. West, A Few Interesting Facts Respecting the Mormons [n.p., 1837], 5), while the other speaks of how the Prophet “translated the characters on the roll, being favored with a ‘special revelation’ whenever any of the characters were missing by reason of mutilation of the roll” (Frederic G. Mather, “The Early Days of Mormonism,” Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science 2, no. 6 [August 1880]: 211). These accounts are in harmony with that published in the Friends’ Weekly Intelligencer but must also be accepted cautiously since they are hearsay.

42. See “Zeptah and Egyptes,” 101–6 herein.

43. See Grey, “‘Word of the Lord in the Original,’” 249–302; Matthew J. Grey, “Approaching Egyptian Papyri through Biblical Language: Joseph Smith’s Use of Hebrew in His Translation of the Book of Abraham,” in MacKay, Ashurst-McGee, and Hauglid, Producing Ancient Scripture, 390–451; and Kerry Muhlestein and Megan Hansen, “‘The Work of Translating’: The Book of Abraham’s Translation Chronology,” in Let Us Reason Together: Essays in Honor of the Life’s Work of Robert L. Millett, ed. J. Spencer Fluhman and Brent L. Top (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University, 2016), 149–53.

44. Jensen and Hauglid, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 334 n. 85.

45. Jensen and Hauglid, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4, 195, 239 n. 57.

46. Gee, Introduction to the Book of Abraham, 143.

47. For an alternative interpretation, see Muhlestein, “Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri,” 29–32; Kerry Muhlestein, “The Explanation-Defying Book of Abraham,” in Hales, Reason for Faith, 82; and Kerry Muhlestein, “Egyptian Papyri and the Book of Abraham: A Faithful, Egyptological Point of View,” in No Weapon Shall Prosper: New Light on Sensitive Issues, ed. Robert L. Millet (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 225–26.

48. See Royal Skousen, “Changes in The Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 11 (2014): 161–76; Marlin K. Jensen, “The Joseph Smith Papers: The Manuscript Revelation Books,” Ensign 39, no. 7 (July 2009): 47–51; and Robin Scott Jensen, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Riley M. Lorimer, eds., “Joseph Smith–Era Publications of Revelations,” in Revelations and Translations, Volume 2: Published Revelations, Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), xix–xxxvi.

49. Nibley, Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri, 63.

50. See, for example, Robert J. Matthews, “Joseph Smith—Translator,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, The Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1993), 77–87; and Richard Lyman Bushman, “Joseph Smith as Translator,” in Believing History: Latter-day Saint Essays, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Jed Woodworth (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 233–47. Some recent authors have taken a different approach to understanding Joseph Smith’s conception of translation. Terryl Givens with Brian M. Hauglid, The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism’s Most Controversial Scripture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 180–202; and Samuel Morris Brown, Joseph Smith’s Translation: The Words and Worlds of Early Mormonism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 193–232, have sought to broaden the definition of “translation” in Joseph Smith’s parlance to effectively equate it with pure revelation, with the end result basically divorcing the text of the Book of Abraham, in this instance, from any relationship with a purported ancient manuscript. For a review and engagement with Givens’s work, see John S. Thompson, “‘We May Not Understand Our Words’: The Book of Abraham and the Concept of Translation in The Pearl of Greatest Price,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 41 (2020): 1–48. Along similar lines, Michael Hubbard MacKay, “The Secular Binary of Joseph Smith’s Translations,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 54, no. 3 (Fall 2021): 1–39, has written on what he sees is the “incommensurability” of translation in Joseph Smith’s thinking, meaning the process of translation ultimately remains inaccessible and indescribable by conventional means and thereby eludes our full understanding.

Figures 14 and 15. “Chapter VI,” Book of Commandments, 1833 (top), and “Section XXXIII,” Doctrine and Covenants, 1835. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The heading to what is today canonized as section 7 of the Doctrine and Covenants in both the 1833 Book of Commandments and the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants identifies this text as both a revelation and a translation.

Figures 14 and 15. “Chapter VI,” Book of Commandments, 1833 (top), and “Section XXXIII,” Doctrine and Covenants, 1835. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The heading to what is today canonized as section 7 of the Doctrine and Covenants in both the 1833 Book of Commandments and the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants identifies this text as both a revelation and a translation. Figure 16. Seer stone associated with Joseph Smith, long side view. Photograph by Welden C. Andersen and Richard E. Turley Jr. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Figure 16. Seer stone associated with Joseph Smith, long side view. Photograph by Welden C. Andersen and Richard E. Turley Jr. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Courtesy Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Figure 17. Replica of Urim and Thummim by Brian Westover. Photograph by Daniel Smith. Courtesy Daniel Smith.

Figure 17. Replica of Urim and Thummim by Brian Westover. Photograph by Daniel Smith. Courtesy Daniel Smith.