Notes

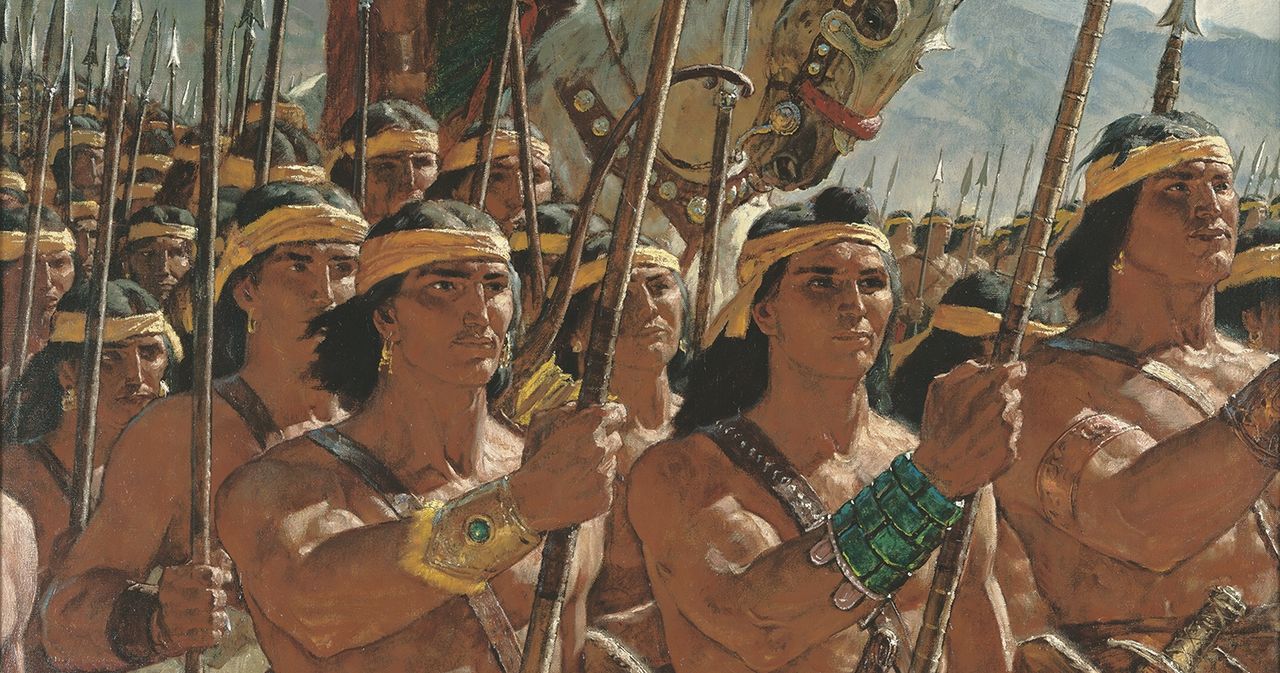

- 1. Part of the reason for the muscular depictions is to show the spiritual strength of the sons through their physical appearance, since there isn’t an obvious way to show their spiritual strength in an illustration. Unfortunately, that imagery can distort our mental picture about their actual appearance. J. David Pulsipher suggests that the muscular depictions of Book of Mormon characters are related to Ezra Taft Benson’s reading of the text. See J. David Pulsipher, “Buried Swords: The Shifting Interpretive Ground of a Beloved Book of Mormon Narrative,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 26, no. 1 (2017): 32.

- 2. “Stripling Warriors Mommas Boys T-Shirt,” BuyLDSproducts.com, updated 2024, https://www.buyldsproducts.com/stripling-warriors-mommas-boys-t-shirt/.

- 3. While the text never identifies the mothers as Anti-Nephi-Lehies, it is an inescapable conclusion from the text. The sons did not enter the covenant to never shed blood again, and the son’s parents were those who did enter the covenant. The mothers and fathers would have had to be married before or shortly after the time of the covenant for the mothers and fathers to have been parents of the stripling soldiers. Since the sons were born at most a few years before and possibly a few years after the covenant, the mothers must have been from among the converted Lamanites, or those who took the new name of Anti-Nephi-Lehi.

- 4. Only two of the four passages in table 1 specifically mention that it is the mothers who taught the stripling sons. The three passages in Alma 56 and 57 are all part of the letter from Helaman to Moroni. Since the description in 57:26–27 follows just a few verses after the attribution in 57:20–21, that description should also be attributed to what the mothers taught. The descriptions in Alma 53 are different because they are from Mormon’s abridgement of the record. However, the shift from the third person account in the first nine verses to the first person in verse ten, “I have somewhat to say concerning the people of Ammon,” makes it difficult to know exactly where the description is coming from. Mormon might be quoting another correspondence from Helaman or from someone else. However, all four passages use the same verb “taught” with similar tenses and phrasing, suggesting that what the sons learned in each description was taught by their mothers.

- 5. In fact, the only use of the word “warriors” in Alma is in Alma 51:31, and it is used specifically to describe Teancum’s men, who were “great warriors” and “did exceed the Lamanites in their strength and in their skill of war.” Nephi quoting Isaiah in 2 Nephi 19:5 is the only other time the word “warrior” appears in the Book of Mormon.

- 6. They are also called “sons of the Ammonites” in Alma 57:6 when Helaman explains that sixty more had come “to join their brethren, my little band of two thousand.”

- 7. American Dictionary of the English Language, s.v. “stripling,” last modified July 7, 2022, https://webstersdictionary1828.com/Dictionary/stripling; Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “stripling, noun,” sense 1, accessed August 1, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/9386524040.

- 8. Anthony Sweat argues that “stripling” could be considered a boy who looks like a “bean pole.” He suggests that because of the way the stripling sons are presented in art, our mental picture of them is much closer to “strapping” young men than “stripling.” “Stripling warriors are . . . boys who haven’t reached manhood. Picture your local congregation’s teacher’s quorum. That is the 2000 stripling warriors.” Anthony Sweat, “History and Art: Mediating the Rocky Relationship,” Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research (FAIR), accessed July 2024, https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/conference/2020-fairmormon-conference/history-and-art.

- 9. Alma 53:18, 20; Alma 56:5, 9, 55 all describe them as “young men.” Alma 57:27 uses “young” and Alma 56:46 calls them “very young.” The only times that the sons are called “men”—in Alma 53:20, 21—are when the characteristics of the soldiers are being described, rather than their age or physical appearance. Of the ten times the Book of Mormon uses the term “young men,” five of them refer specifically to the stripling soldiers (Alma 53:18, 20; 56:5, 9, 55). Other than those five references, the term “young men” is only used once in reference to soldiers in Mosiah 10:9. The other four references to “young men” are 2 Nephi 19:17; 23:18; Mosiah 2:40; and 3 Nephi 2:16. The two references in 2 Nephi are part of the Isaiah chapters and seem to both be included in groups who are powerless against destruction. In Mosiah 2:40, the young men are in a list with old men and little children, which could suggest that “young men” refers to everyone who is not a child and not old—that is, males in their twenties or thirties who might already be married and have children. Third Nephi 2:16 talks about the young men and young women of Lamanite descent who are numbered among the Nephites. The specific mention that these young men and women are “exceedingly fair” suggests that they are of marriageable age, but not yet married or perhaps very recently married. (1 Nephi 11:13 and Ether 8:9 also suggest that the term “exceedingly fair” refers to someone who is of marriageable age, but not yet married.) Given these five usages, it seems more likely that “young men” refers to males who are not children, but not yet mature adults.

10. John Welch has argued that the sons were 20 to 22: “Since the term young men in the Book of Mormon almost always refers to soldiers, it is reasonable to conclude that a ‘young man’ under Nephite law and society was a man who had attained the age of twenty and who was responsible to render military service. (The Hebrew terms bahurim and necurîm refer precisely to such young men liable for military service.)” John W. Welch, “Law and War in the Book of Mormon,” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and William J. Hamblin (Deseret Book; Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1990), 65–66, italics original. Stephen Ricks agrees with this assessment in his chapter: “‘Holy War’: The Sacral Ideology of War in the Book of Mormon and in the Ancient Near East,” in Ricks and Hamblin, Warfare in the Book of Mormon, 109. John A. Tvedtnes also follows this number in “What Were the Ages of Helaman’s ‘Stripling Warriors’?” Ensign 22, no. 9 (September 1992): 28. The assumption for this argument is that the army is made up of sons who were not old enough to make the covenant their parents did, but who have since come into the age of military service.

The difficulty of this assumption is that the text does not state the specifics of the oath, whether it was taken by adults of a certain age, only by men, or only by men of military age or by every one of the converts. If the oath required a verbal pronouncement, children too young to speak would not have taken the oath. However, if the oath applied only to adults at the time of the oath, then many of the younger boys would have come of age during the many years of war since the Anti-Nephi-Lehies made the oath. The wording of Alma 53:14 suggests that all the men who would be of typical military age during these many years of war were all considered to be bound by the oath. The “many sons, who had not entered into a covenant” (Alma 53:15) were most likely those who were too young to say the words of the oath or had not yet been born when the oath was taken. This is complicated because the text does not tell us the exact year when the oath was taken, but we know that it was taken before the sacking of Ammonihah in the eleventh year of the reign of the judges.

- 11. Grant Hardy, The Annotated Book of Mormon (Oxford University, 2023), 470 n. 16.

- 12. See Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, vol. 4, Alma (Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 353–55, and 686 with n. 4.

- 13. Some of the women may have been in their teens, a few even pre-teens, during the events described in Alma 23–28, but they were old enough to be having children, so I have included them in the category of “adults.” Unfortunately, we know very little about Lehite marriage ages. When Lehi and Sariah left Jerusalem, they had four unmarried sons. Because all the sons were unmarried when they left, but all were married simultaneously in the wilderness, they were likely between ages 12 and 18. Sariah also has daughters and two more sons in the wilderness, so she could have been having children into her 40s. Some ancient cultures do marry girls as young as 12 who have children by 13. If the Lamanites had a lower marriageable age of 12, and if the “stripling” son was the mother’s first child, born a year after marriage, and was one of the youngest warriors (12 years old), the youngest mothers of the stripling soldiers would have been 25 when their sons went to war. If the mother was on the oldest end and gave birth to the son later in life, in mid-40s, and her son was one of the older soldiers, maybe 16, then the oldest of the mothers would have been around age 60. This puts the youngest of the mothers born around the third year of King Mosiah’s sons’ mission, and the oldest of the mothers could have been born up to thirty years before the missions started. These edges of the age range are not likely the most common for the mothers; the average age would probably be on the lower end with the mothers being in their late 20s or early 30s when their sons went to war, so most of them were likely born several years before the missions started or a few years after. This puts the mothers in their late teens to mid-thirties in the eleventh year of the reign of the judges.

- 14. Helaman 3:12 is the last specific mention of the people of Ammon. It tells that during the forty-sixth year of the reign of the judges, they were part of those who went forth into outlying lands.

- 15. Ammon and his brethren’s missions began in the first year of the reign of the judges (Alma 17:6). Their missions last fourteen years (Alma 17:4) and the war precipitated by the Ammonite conversion ends in the fifteenth year of the reign of the judges. Presumably, the missionaries returned and reunited with Alma in the fourteenth year of the reign of the judges (Alma 17:1 and Alma 28:7). The heading to Alma 17 states that the section is “an account of the sons of Mosiah . . . according to the record of Alma.” The wording of Helaman 3:12–13 seems to suggest that the Anti-Nephi-Lehi people kept records of their own, which could have been a source for Alma. If their records did not include timestamps, it would explain why Mormon was not able to include any.

- 16. This timestamp is important because the same Lamanites who massacred the Anti-Nephi-Lehies (Alma 25:2) are those who leave and sack Ammonihah (Alma 16:9). Alma 16:21 points to the end of the fourteenth year, and this is before Alma is reunited with Ammon and his brethren.

- 17. Brant Gardner discusses the difficulty that the Lamanites return in the fourteenth year (Alma 16:12), and that the same battle is described in Alma 28:1–7 as concluding at the end of the fifteenth year. See Gardner, Alma, 390–92, especially 391.

- 18. Even this year is a little bit difficult to know for sure. According to Helaman’s letter to Moroni, the sons go to war in the twenty-sixth year of the reign of the judges (Alma 56:9). However, in Mormon’s abridgement of the record, the twenty-sixth year happens in Alma 52:1–14, where the stripling sons are not mentioned. It is in Alma 53:10–23 when the stripling sons are introduced in Mormon’s narrative, and the timestamp given at the end of that chapter is the end of the twenty-eighth year. In the twenty-sixth year, the war is very dire (Alma 52:14), so it may correspond to when the stripling sons gather and go to help Antipus, even though Mormon does not mention them until the twenty-eighth year.

19. Though I use the term “Anti-Nephi-Lehies” in this article because it is commonly used, I prefer the name “Anti-Nephi-Lehites” for this group of people as a whole instead of “Anti-Nephi-Lehies” or “Ammonites.” The Nephites refer to these Lamanite converts as “the people of Ammon” and that name is used a total of nineteen times (Alma 27:26; 28:1; 30:1, 19; 35:8–11, 13; Alma 43:11, 13; 47:29; 53:10; 58:39; 62:17, 27, 29; Hel. 3:12). The sons are called “stripling Ammonites” and “sons of the Ammonites” in Alma 56:57 and 57:6 respectively. Since the Book of Mormon regularly uses “ites” as a suffix meaning “people of,” Ammonites is a reasonable name for this people. However, “Ammon” is not the name that the people chose for and took upon themselves.

In Alma 23:16–17, when the group desires a new name to distinguish themselves from those who were not converted, they chose the name “Anti-Nephi-Lehi.” “Anti-Nephi-Lehi” is the name of the king who succeeds King Lamoni’s father (Alma 24:4–5). The people chose this name for themselves and “they called their names Anti-Nephi-Lehies” (Alma 23:17, emphasis added). It is significant that the word “names” is plural and that “Anti-Nephi-Lehies” is also plural here. It seems that each individual took upon themselves the name “Anti-Nephi-Lehi.” This is how the name is also used in Alma 24:1, where those “who had not been converted . . . had not taken upon them the name of Anti-Nephi-Lehi.” Because of the plural use, “Anti-Nephi-Lehies” in Alma 23:17, it has become common to use that plural to designate the group as a whole.

Since the Book of Mormon does not use a similar type of plural for other groups of people, the name “Anti-Nephi-Lehies” could be a plural use of “Anti-Nephi-Lehi,” meaning that multiple people have that same name, rather than the name of the group as a whole. When discussing multiple individuals with the same name, the name is pluralized without being the name of a specific group, for example there are four Nephies, two Josephs, two Helamans, and two Mormons in the Book of Mormon. This is a list of individuals who share a name, but not a group who are a distinct people. Mosiah 25:12 gives a specific example of a how the children of Amulon and his brethren take the name Nephi “they might be called the children of Nephi and be numbered among those who were called Nephites.” This pattern is attested numerous times in the Book of Mormon as it uses Nephites as a name for the people of Nephi, Lamanites for the peoples of Laman, and “Jacobites, Josephites, Zoramites, Lamanites, Lemuelites, and Ishmaelites” for the people of those families (Jacob 1:13–14, see also 4 Ne. 1:36–38 and Morm. 1:8–9).

In addition to calling this group “the people of Ammon,” the Book of Mormon uses the phrase “the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi” eight times (Alma 24:2, 12; 25:1, 13, 27:2, 21, 25; 43:1). Because they are specified as a “people of” and the name “Anti-Nephi-Lehi” is the name they chose and took upon themselves, it seems appropriate to use an “-ites” suffix with that name. Since the name “Anti-Nephi-Lehies” does not coordinate them with the other specific and recognizable groups in the Book of Mormon, I think that “Anti-Nephi-Lehites” is a better designation for them. The Book of Mormon does not use the words “Lehites” or “Limhites,” but these names are sometimes used to refer to all Lehi’s descendants or to Limhi’s people. In a similar way, I think the term “Anti-Nephi-Lehites” is a more useful designation for the “people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi.”

20. It’s notable that the story of the Anti-Nephi-Lehi people starts with a story where two other women are central, Abish and King Lamoni’s wife, in Alma 19. For an exemplary analysis of this story and its effect on Lehite history, see Nicholas J. Frederick and Joseph M. Spencer, “John 11 in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of the Bible and Its Reception 5, no. 1 (2018): 81–105, https://doi-org.byu.idm.oclc.org/10.1515/jbr-2016-0025.

The Book of Mormon does not say when King Lamoni’s and his father’s conversions happened during Ammon’s fourteen-year mission or how long it was between the kings’ conversions and the following conversions of the other Lamanite areas. George Reynolds suggests that it is “probable that the conversion of king Lamoni took place in the first year of their ministry.” George Reynolds, The Story of the Book of Mormon (Joseph Hyrum Parry, 1888), 141. However, a comparison to Aaron’s journeys makes that seem unlikely. Aaron teaches in the city of Jerusalem (Alma 21:1), then goes to Ani-Anti (21:11), and then to the land of Middoni (Alma 21:12) where he is cast into prison. He is delivered out of prison by Ammon and King Lamoni. Ammon’s travels to three different cities could have happened within the first year of the missions, but they could also have taken several years. Brant Gardner suggests that Mormon has compressed the timeframe of Ammon’s experiences in order to easily coordinate with the other missionaries’ stories and to tell Ammon’s story more efficiently. Gardner, Alma, 319. This suggests that Lamoni’s conversion was in the earlier years of the mission, maybe between the third and fifth, but not necessarily in the first year.

- 21. The list in Alma 23:8–12 contains seven places and names some of them “lands” and some “cities.” The lands are the lands of Ishmael, Middoni, Shilom, and Shemlon. The cities are the cities of Nephi, Lemuel, and Shimnilom.

- 22. John Welch suggests that the name meant “Non-Nephite Lehies.” John W. Welch, Inspirations and Insights from the Book of Mormon: A Come, Follow Me Commentary (Covenant, 2023), 177. For more on the meaning of the name “Anti-Nephi-Lehi,” see Hardy, Annotated Book of Mormon, 380; Hugh Nibley, quoted in Daniel Ludlow, A Companion to Your Study of the Book of Mormon (Deseret Book, 1976), 209–10; Gordon C. Thomasson, “What’s in a Name? Book of Mormon Language, Name, and Metonymic Naming,” JBMS 3, no. 1 (Spring 1994):14–15; Stephen D. Ricks, “Anti-Nephi-Lehi,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Deseret Book, 2003), 67.

- 23. Alma 24:2 says that these people “took up arms against the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi,” but it does not specify if this refers to earlier violence that happened while King Lamoni’s father was alive and reigning or if it refers to the violence described in Alma 24:20 after King Anti-Nephi-Lehi became king.

- 24. In Alma 24:1–2, these people are also specified by their lands, specifically, Amulon, Helam, and Jerusalem, but they also include those “in all the land about, who had not converted.” See also Alma 25:13 when some of the Lamanites coming home from sacking Ammonihah return to Ishmael and Nephi, areas that are listed as converted in Alma 23:8–12. Gardner suggests that the Anti-Nephi-Lehies migrated to a single location from the seven areas listed, given that they seem to fit into one city or area when they move to Nephite territory. This would also explain how and why it was possible for the other Lamanites to come against them so easily. Gardner, Alma, 346.

- 25. While it is impossible to know when or where any of the mothers joined with the converts, there is no indication that anyone joined the Anti-Nephi-Lehi people from when they decided to leave Lamanite territory to when the Zoramites join them several years later. Theoretically, some of the mothers could have come from outside the Anti-Nephi-Lehies and joined the group later. However, all the women who became the mothers of the stripling soldiers were married to men who covenanted not to shed blood, so they must have been part of the Anti-Nephi-Lehies by the time they left Lamanite territory. In Alma 53:10–16, which explains the oath of the Anti-Nephi-Lehies, it is “the people of Ammon” in verse 10 who are the “they” “who had many sons” in verse 16, suggesting that the parents of the sons were all part of the Anti-Nephi-Lehi people before they left Lamanite territory.

- 26. The text doesn’t specify the role of the women in these decisions, covenants, or the bloodshed. Perhaps those who went out and prostrated themselves were only the men who would have otherwise been fighting, but perhaps there were women and children as well. Alma 24:21 says that the “people” saw the Lamanites coming against them and “they went out to meet them,” suggesting that the group could have been all of the people. However, verse 23 says that “the Lamanites saw that their brethren would not flee,” suggesting that it was more likely the military-aged men who prostrated themselves.

- 27. This group’s conversion is a little more indirect than the others. Some of the Lamanites who had gone to Ammonihah become disenchanted and are “stirred up in remembrance of the words which Aaron and his brethren had preached to them in their land” and are “converted in the wilderness” (Alma 25:6). These wilderness converts, however, were never able to join the Anti-Nephi-Lehies because they were executed by their fellow soldiers while still in the wilderness (Alma 25:7). But others of their company, when seeing those executions, were “stirred up to anger” (Alma 25:8) and hunted the executors. A group of these Lamanites returned to their own lands, “did join themselves to the people of God, who were the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi,” and buried their weapons of war (Alma 25:13).

- 28. There are two other additions to the Anti-Nephi-Lehi people: the displaced Zoramites (Alma 32:2, 6), and the “large body” of Lamanite men conquered by Moroni’s army (thirty-first year of the judges, Alma 62:15–17). Neither of these groups would have been part of the stripling soldiers. Zoramites who could serve in the army probably would have joined earlier than the stripling soldiers, and the conquered Lamanite men would have joined the Anti-Nephi-Lehies toward the end of the war.

- 29. This promise comes after the return from Ammonihah (Alma 16:1–3, 12) but before the reunion between Alma and the missionaries (Alma 17:1–2), putting it sometime after the eleventh year of the reign of the judges and before the fourteenth year of the reign of the judges.

- 30. In a letter to Captain Moroni, one of Helaman’s arguments for allowing the stripling soldiers to fight was that the Anti-Nephi-Lehies were descended from the Lehite lineage. Alma 56:3 “now ye have known that these were descendants of Laman, who was the eldest son of our father Lehi.”

- 31. While we do not have any details from the Book of Mormon about the Anti-Nephi-Lehi traveling experience, the practice of stealing, robbing, and plundering seems to have been common between different groups of Lamanites and unrighteous Nephites. For example, when Ammon was guarding the king’s flocks in Alma 18:7, it reads, “it was the practice of these Lamanites to stand by the waters of Sebus to scatter the flocks . . . it being a practice of plunder among them” (see also Alma 17:14, 23:3, 50:21). However, we cannot always take Mormon’s descriptions of the Lamanites at face value. For an informed perspective on this, see Jan J. Martin, “Samuel the Lamanite: Confronting the Wall of Nephite Prejudice,” in Samuel the Lamanite: That Ye Might Believe, ed. Charles Swift (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2021), 107–52.

- 32. John W. Welch and J. Gregory Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon: Visual Aids for Personal Study and Teaching (Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1999), chart 136.

- 33. Welch and Welch, Charting the Book of Mormon, chart 137.

- 34. After the accounts of the stripling soldiers in Alma 53 and 56–58, the Book of Mormon does not tell us more about the Anti-Nephi-Lehi people except for a mention in Helaman 3:12 that the people of Ammon were part of a group who go into “the land northward.”

- 35. In this portion of the Book of Mormon text, the women as mothers is an important part of their identity and contribution. I do not want to reduce all women and their contributions to their reproductive functions. I also do not want to minimize the complexities of being a woman disciple—mother or not. I don’t want to be insensitive to other situations, but I do want to focus on this specific text, so the discussion is centered around these women as mothers. Pregnancy is a distinct experience that is limited and outside of some people’s experience. Most women who are mothers were at some point pregnant. It is certainly possible that some of the sons could have been adopted or raised by a nonbiological mother given the violence their people were experiencing when these sons were being raised. However, it’s a reasonably safe assumption that most mothers of the stripling soldiers were pregnant with, gave birth to, nursed, and raised the sons who joined Helaman’s army.

36. The other mention of fathers is in Alma 56:47, where both fathers and mothers are mentioned: “They did think more upon the liberty of their fathers than they did upon their lives; yea, they had been taught by their mothers, that if they did not doubt, God would deliver them.”

Eighteen of the twenty uses of two thousand in the Book of Mormon are in Alma 53, and 56–58. (The other two are 3 Nephi 17:25, “two thousand and five hundred souls,” and Mormon 2:9, “forty and two thousand.”) Two thousand seems to be a standard number for a group of Nephite soldiers, though the number could mean more a type of group than an exact count of soldiers.

- 37. There are eighty-seven women or groups of women in the Book of Mormon. See Heather Farrell and Mandy Jane Williams, Walking with the Women of the Book of Mormon (Cedar Fort, 2019) and Wendy Hamilton Christian, “‘And Well She Can Persuade’: The Power and Presence of Women in the Book of Mormon” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2002), https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4597. For a bibliography about gender in the Book of Mormon see Daniel Becerra and others, Book of Mormon Studies: An Introduction and Guide (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2022), 151–52.

- 38. This situation of the sons is an interesting parallel to the experience of their parents leaving their homeland. Both groups were leaving an area while being pursued by a Lamanite army. The parents had made a covenant not to fight and left their homes so they would not be killed; the sons were facing an army that was superior to theirs in numbers and strength. Both groups were delivered from the army pursuing them. The Anti-Nephi-Lehi parents were delivered by being given a safe haven in Nephite lands and by the Nephite army protecting them. The sons were delivered because Antipus’s army was able to catch up to the Lamanite army and start fighting. The parallel situation is also interesting because of the reverse parallel of each groups’ covenant. The parents had promised not to take up arms even in defense; the sons had promised to fight to their deaths.

- 39. By chapter 58, Helaman recounts the attitude of the whole army being aligned with the faith of the stripling sons. Alma 58:11–12 states, “the Lord our God did visit us with assurances that he would deliver us; yea, insomuch that he did speak peace to our souls, and did grant unto us great faith, and did cause us that we should hope for our deliverance in him. And we did take courage with our small force which we had received, and were fixed with a determination to conquer our enemies, and to maintain our lands, and our possessions, and our wives, and our children, and the cause of our liberty.” It is notable that this campaign to retake the city of Manti was also accomplished “without the shedding of blood” (Alma 58:28).

- 40. When considering the casualties of Antipus’ army Helaman stated, “We may console ourselves in this point, that they have died in the cause of their country and of their God, yea, and they are happy” (Alma 56:11). See Alma 21:9 and Alma 22:13–14 for Aaron’s teachings to king Lamoni’s father, which were presumably also taught to the other converts, about the coming of Christ, the resurrection, the atonement, and that “the grave shall have no victory, and that the sting of death should be swallowed up in the hopes of glory.”

- 41. Mormon states this about all the Nephites who mourned the loss of someone killed in the battle of Jershon and would presumably apply to all the faithful when they die, whether or not in battle, including the Anti-Nephi-Lehies who “never did fall away” (Alma 23:6).

- 42. All art in this article can be found on the Book of Mormon Art Catalog website: https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org.

Their Mothers Taught Them by Brent Borup, graphite with digital coloring, 2020, by permission of the artist.

Their Mothers Taught Them by Brent Borup, graphite with digital coloring, 2020, by permission of the artist. Figure 1. T-shirt the author saw in Orem High School, Orem, Utah. Courtesy

Figure 1. T-shirt the author saw in Orem High School, Orem, Utah. Courtesy  Figure 2. Helaman’s Stripling Warriors, by Arnold Friberg, 1952–55, cropped. © By Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Figure 2. Helaman’s Stripling Warriors, by Arnold Friberg, 1952–55, cropped. © By Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Figure 3. “Stripling Warrior Action Figure” at Deseret Book. Courtesy Latter Day Designs.

Figure 3. “Stripling Warrior Action Figure” at Deseret Book. Courtesy Latter Day Designs. Stripling Warriors by Jody Livingston, mixed media, 2016, by permission of the artist.

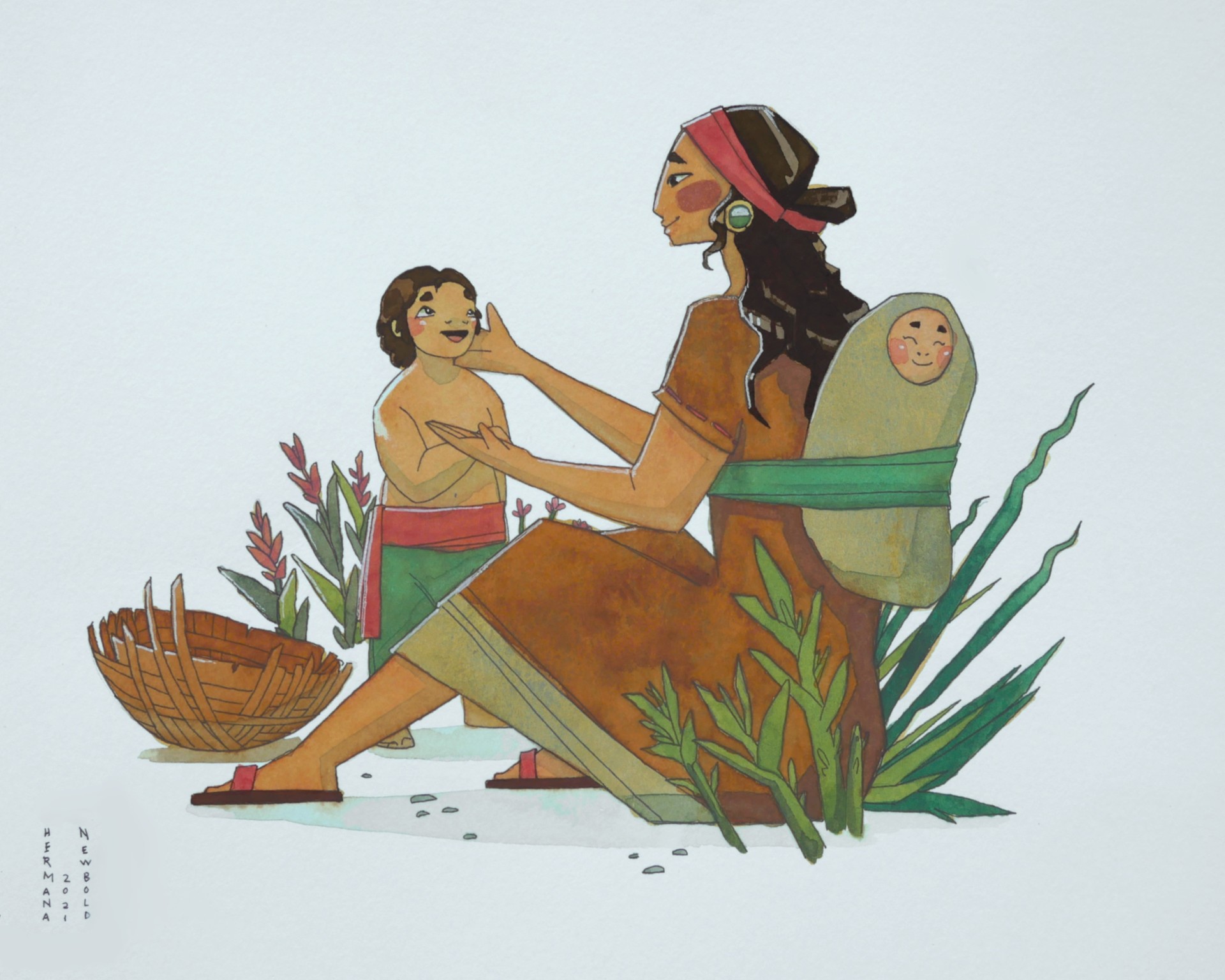

Stripling Warriors by Jody Livingston, mixed media, 2016, by permission of the artist. Anti-Nephi-Lehi Mother and Her Stripling Warrior by Sierra Newbold; ink, watercolor, and markers; 2021; by permission of the artist.

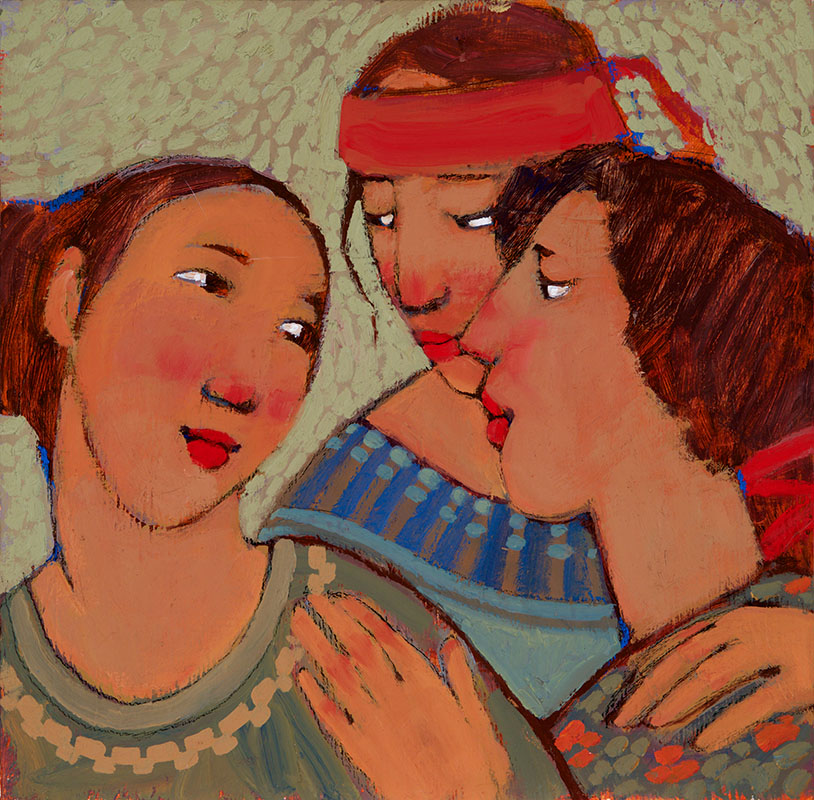

Anti-Nephi-Lehi Mother and Her Stripling Warrior by Sierra Newbold; ink, watercolor, and markers; 2021; by permission of the artist. Our Mothers Knew It by Megan Rieker, oil on canvas, 2017, by permission of the artist.

Our Mothers Knew It by Megan Rieker, oil on canvas, 2017, by permission of the artist. Helaman’s Army Preparing for Battle by Jorge Cocco Santángelo, oil on canvas, 2023, by permission of the artist.

Helaman’s Army Preparing for Battle by Jorge Cocco Santángelo, oil on canvas, 2023, by permission of the artist. Stripling Warrior Mothers by Kathleen Peterson, oil, 2015, by permission of the artist.

Stripling Warrior Mothers by Kathleen Peterson, oil, 2015, by permission of the artist. Mothers of the Stripling Warriors by Kathleen Peterson, oil, 2015, by permission of the artist.

Mothers of the Stripling Warriors by Kathleen Peterson, oil, 2015, by permission of the artist. Mother Knew, generated using MidJourney by Ethan Smith, 2023, by permission of the artist.

Mother Knew, generated using MidJourney by Ethan Smith, 2023, by permission of the artist.